Post 4: Why Penal Substitution is a Gateway Drug to Right-Wing Extremism

Grafting of a tree branch. Photo credit: Helger11/74, Pixabay License.

How Penal Substitutionary Atonement Can Be Grafted Onto an Unjust Social Order

A tree branch can be cut off its native tree and grafted onto another. In the same way, penal substitutionary atonement can be cut off its native Lutheran and Calvinist tree. It can be easily grafted into a theological and political system which is virulently racist, as did happen in South Africa and the United States. Why is that? Because penal substitution can sit all too comfortably on a defective view of creation.

In addition, this branch behaves in an unusual way. The branch can reverse the typical flow of influence. It can reach backward into its supporting structure and further poison the tree. In other words, penal substitution sits on top of Scripture, but it affects the way people read Scripture in its entirety.

Abolitionist Creation Theology from the Early Church

Let me first give an example from the early church. Watch for the healthy interaction between a truly biblical doctrine of creation and the medical substitution atonement theory.

In the late fourth century, the outstanding Cappadocian theologian and bishop Gregory of Nyssa preached and wrote scathing critiques of slavery founded on the doctrine of creation:

‘You condemn a person to slavery whose nature is free and independent, and in doing so you lay down a law in opposition to God, overturning the natural law established by him. For you subject to the yoke of slavery one who was created precisely to be a master of the earth, and who was ordained to rule by the creator, as if you were deliberately attacking and fighting against the divine command… What price did you put on reason? How many obols did you pay as a fair price for the image of God? For how many staters have you sold the nature specially formed by God? God said, Let us make man in our image and likeness.’[1]

According to Gregory’s reading of Genesis 1, God made every human being to share in the wealth of creation. So for a master/employer to claim in principle the material wealth of a slave/indentured servant is to violate the order of creation. To enslave another person, according to Gregory, is to obstruct God’s intention for that person, which is: ‘precisely to be a master of the earth, and who was ordained to rule by the creator.’ Gregory’s references to ‘nature’ and ‘the natural law’ and ‘the nature specially formed’ find their anchor point not in some kind of scientific or philosophical exploration independent of Scripture and Christian theology, but in ‘the creator,’ the one identified as ‘God’ who has given ‘the divine command.’ The totality of nature, human beings included, is nothing less than God’s creation, as defined by the biblical narrative. Gregory’s quotation of Genesis 1:26 makes that indisputable. God made us to inhabit His relational vision of co-ruling the creation. So who are we to obstruct it?

What about all the biblical passages which seem to accept ‘slavery’? There is limited data from Gregory himself about his reading of these passages. But from my understanding of Scripture[2] and my readings of other patristic writers and church history,[3] I suspect that in the world of late Roman antiquity, slavery to a household to pay back legitimate financial debt and/or a penal debt was still generally acceptable to Christians, and to Gregory. However, forcibly kidnapping and enslaving someone was strictly forbidden in both Old and New Testaments (Ex.21:16; Dt.24:7; 1 Tim.1:10), while escaping runaways were to be assisted (Dt.23:15 – 16). Since Israel’s life in their garden land was a partial restoration of Adam and Eve’s life in the original garden land, then this data from the Sinai covenant affirms Gregory’s anti-slavery position based on the creation narrative. Why Gregory didn’t mention the particular causes of enslavement seems simple enough to explain: I don’t think Gregory needed to spell out the caveats in detail, especially in preached homilies. Thus, Gregory’s voice is sometimes held up, in my opinion, as being a bit too unique in church history.[4]

Be that as it may, I think Gregory of Nyssa is fundamentally correct about how to understand the creation order in Genesis, even including the caveats, as the exceptions seem to prove the rule in Scripture itself. If God intended for every human being to bear His image, then He also intended for every human being to reign as His representative in creation. This means both a share in creation’s material wealth, and the relational obligation to share the wealth of creation with others. For if God shares the nourishment and wealth of creation us as human beings, we who bear God’s image must do the same.

Consider also God’s original design for marriage, also from the creation narrative. God’s vision for marriage required a man to leave his father and mother to join his wife (Gen.2:24). For a husband to place his priority on his wife over his parents was the subversion of patriarchal systems. Patriarchy manifested itself in the line of rebellious Cain (Gen.4:16 – 24). But Israel was God’s partial restoration of humanity to a garden land, especially for every newly married couple, who would inherit their ‘portion’ of the garden land.[5]

Furthermore, in a sermon during Lent in the year 397 AD, Gregory also saw God’s gift of creation as reiterated and confirmed by the gift of Christ:

‘Since God’s greatest gift to us is the perfect liberty vouchsafed us by Christ’s saving action in time, and since God’s gifts are entirely irrevocable, it lies not even in God’s power to enslave men and women.’[6]

By saying that ‘God’s gifts are entirely irrevocable,’ Gregory testifies to God’s generous and gracious movement from creation to new creation being connected and cumulative. Once again, this connection between creation and new creation in Christ, humanity in Adam and new humanity in Christ, is common and well established in patristic thought. The fact that Gregory of Nyssa now deploys it against enslavement demonstrates the robustness of Christian theology and ethics flowing from this period.

Also, the doctrine of creation is directly involved in the doctrine of atonement. What is God’s objective in atonement? To undo self-harm. Gregory of Nyssa taught new Christians this way:

‘If, then, love of man be a special characteristic of the Divine nature, here is the reason for which you are in search, here is the cause of the presence of God among men. Our diseased nature needed a healer. Man in his fall needed one to set him upright. He who had lost the gift of life stood in need of a life-giver, and he who had dropped away from his fellowship with good wanted one who would lead him back to good. He who was shut up in darkness longed for the presence of the light. The captive sought for a ransomer, the fettered prisoner for someone to take his part, and for a deliverer he who was held in the bondage of slavery.’[7]

Gregory’s contemporary and fellow bishop Augustine of Hippo said:

‘[It is] perverse… to imagine that our enemies can do us more harm than we do to ourselves by hating them, or that by persecuting another man we can damage him more fatally than we damage our own hearts in the process.’[8]

This was ‘salvation’ to Gregory of Nyssa, Augustine of Hippo, and the other theologians in both the Greek and Latin traditions. How do we see that in Scripture? What we notice from the Genesis narrative is that sin’s most lasting and perilous impact is self-harm. Adam and Eve corrupted human nature and alienated themselves from God, each other, and the land (Gen.3:16 – 24); Cain corrupted himself further and was unable to call forth life from the land (Gen.4:10 – 12); God diagnosed the problem as a corruption in the human heart (Gen.6:5 – 6; 8:21). While sin is undeniably expressed or identified by the breaking of commandments and injury to others, fundamentally, sin is damage to one’s own self, and God’s forgiveness in Christ is a declaration of pardon for the damage we have inflicted upon our own human nature, we who are the artistic masterpieces God treasures. I might do incredible and lethal damage to another person’s body, and that is grievous and evil. But God can heal that person’s physical body. If I damage my own will and nature in the process of harming another or resisting God, God can heal that, too, but only with my partnership and full participation in Jesus.

Also, when Gregory says, ‘Our diseased nature needed a healer… The captive sought for a ransomer, the fettered prisoner for someone to take his part, and for a deliverer he who was held in the bondage of slavery,’ he refers to Paul’s personal experience. In Romans, Paul spoke of being in bondage to ‘the sin which indwells’ his own body (Rom.7:7 – 25), and needing Christ Jesus to indwell him by the Spirit, freeing the true self from bondage. Why was Jesus qualified to do this? Because Jesus was the only one who completely condemned the sin in his own flesh, more specifically by never sinning (Rom.8:3). He healed, delivered, and saved his own humanity. That is what qualifies him alone to heal, deliver, and save ours by his Spirit.

In other words, in the ontological-medical substitution paradigm, we must immediately – and of necessity – reflect on the biblical account of creation. In this view, Jesus is restoring all humanity to what He designed human beings to be: relational bearers of His image and likeness. By speaking of the ‘image of God,’ we must turn to Genesis 1. We are also required to reflect on God’s intentions from creation for all human relationships. In Christ, there is a relational vision still shining from creation and renewed by him, not just regarding marriage (Mt.19:3 – 12; Mk.10:1 – 12), but all types of human relationships. Regarding economic relationships, Jesus refers to the ‘regeneration,’ (Mt.19:28) or the ‘re-genesis,’ in his encounter with the rich young ruler (Mt.19:13 – 30; cf. Mk.10:13 – 31), indicating that incredible generosity was what God intended from creation. We can consider how Israel’s life in their garden land was a partial restoration of the original creation as well. The Sinai covenant’s concessions to Israel’s ‘hardness of heart,’ discussed by Jesus as a wider tolerance for divorce (Dt.24:1 – 4) and apparently a wider tolerance for family land possession, was being overcome because Jesus was overcoming ‘hardness of heart’ itself.

This teaching was characteristic of the church for over a thousand years. Atonement as an ontological-medical act is God’s solution to the internal damage in human nature, the resistance of the human will to God, and the disruption of God’s good created order. The wrath of God is directed at the disease of sin, not at the personhood of the human being. This paradigm explains why Jesus introduced ‘forgiveness of sin’ language in his ministry when he raised up the paralytic (Mt.9:1 – 9; Mk.2:1 – 12; Lk.5:17 – 26). The phrase is better translated ‘release from sin’ or ‘remission of sin,’ where sin is being physically portrayed as the paralysis, or bondage, of the man’s body (though not synonymous with it, as paralysis did not indicate that he was more sinful than anyone else). God forgives us not for breaking laws which only exist in His own mind. He forgives us for breaking laws which are written on our human nature, which were designed to nurture human relationships, which inhere in human existence whether we recognize it or not. So of course God forgives us in Christ for the damage we have done to ourselves. For in Christ, He restores us to who we were meant to be.

Creation Theology and Ethics in the U.S. and South Africa

Sadly, however, evangelical Christians moved away from a clear understanding of the biblical creation account with its robust relational vision, exemplified here by Gregory of Nyssa. They gave other accounts of creation in its place. This theological problem played out not just in the United States, but also in South Africa under the Dutch Reformed. They believed ‘Afrikaner Calvinism,’ in which God made the races to be distinct from creation, and the Dutch Boer whites were a new kind of ‘chosen people,’ eventually resulting in Apartheid.[9] My point here is not to blame Calvin for Apartheid (which I do not). My point is simply to make visible how easily penal substitutionary atonement can freely float onto an unbiblical creation theology and sit there comfortably.

Similarly, American racial slavery was also seen as a holy social order ordained by God, with ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders,’ against which even the British crown should not interfere. Hence the myth of the American Revolution: the theory of the revolutionaries’ noble intentions hides their anxiety about losing their slaves. The black community, and especially the black male, was blamed and scapegoated for any disturbance of that social order as if they were treasonous terrorists sent by the British crown to take away white American liberty. Even if the equality of the races had been the acknowledged starting point, I am doubtful that penal substitution and its enshrinement of the retributive justice principle would have done much to engage the biblical misinterpretation of ‘slavery,’ shape the definition of what counts as a crime, moderate the severity of civil punishment, shape in what way a non-citizen ‘outsider’ should be treated in the same way as a citizen, or moderate the severity of civil punishments.

This is still relevant because American evangelicals are not out of the woods of this danger. Some evangelicals continue to make the same mistake about the socio-political order in new ways. Here are three examples.

Mistake #1 of Modern Evangelicals: The Trinity is a Hierarchy of Power

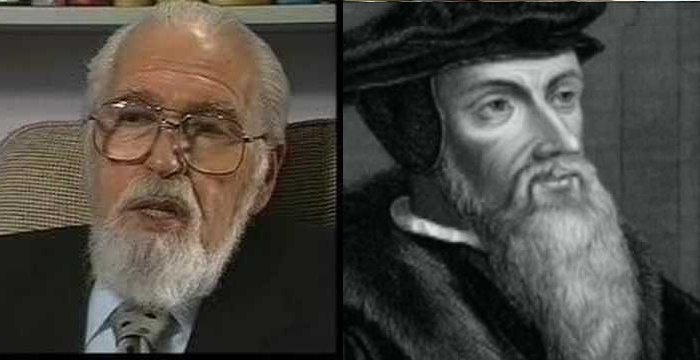

First, take Reformed voices like C. Michael Patton and Mark Driscoll (don’t they look alike?) who argue that hierarchies in society are needed reflections of hierarchy in the Trinity:

‘While I don’t believe there is an ontological hierarchy (gradation of essence, or all that stuff I said above), I do believe there can be a hierarchy in person. In other words, one member of the Trinity can take on a different rank than another. I think we can all agree that at the incarnation, this hierarchy presented itself as Father, then Son, then Spirit. After all, even Christ said that the Father was greater than he was (John 14:28). This is sometimes called a “functional hierarchy.” This should not be too difficult to process, as we can see many analogies to this in our own world. For example, President Obama is greater than I am in one respect. He is the President of the United States. Therefore, his position and authority are greater than mine. But he is not greater in essence. Similarly, parents are greater than children in rank. But they are not greater in their being. And (cover your eyes, egalitarians) I believe the Bible presents the husband as having greater authority than his wife. However, he is not greater in his ontos or humanity… When it comes to the Holy Spirit, I believe the Holy Spirit is last on the divine authority totem pole. The Father sends the Son, the Son sends the Holy Spirit, and the Father is sent by none.’[10]

It is difficult to catalogue Patton’s assumptions here, and why this is so disconcerting.[11] For my purpose here, I think it sufficient to call attention to two facts. First, the New Testament authors never reason out Christian ethics this way. The apostles do call us to imitate the humility and personal sacrifice of the Son of God, shown by his willingness to become incarnate as the human Jesus (e.g. Phil.2:5 – 11; 2 Cor.8:9), or his love for others, shown by Jesus’ voluntary crucifixion and death (e.g. Eph.5:25 – 33; 1 Pet.2:20 – 25). But they always draw on activity which was or became visible in the life of Christ. They did not extrapolate from the invisible mystery of the Trinitarian relations.

The boundary case might be 1 Corinthians 11:3.

‘Christ is the head of every aner (meaning ‘man,’ which might be inclusive of women, or meaning ‘husband,’ depending on the context), and the aner (husband?) is the head of a gyne (woman or wife), and God is the head of Christ.’ (1 Cor.11:3)

But even here, the fact of Christ’s incarnation and historic visibility is paramount. And what does the term ‘head’ mean here? I believe the significance of the head is as the organ of speech, as shown when God spoke to Moses who spoke to Aaron who spoke to the people:

‘Moreover, he shall speak for you to the people; and he will be as a mouth for you and you will be as God to him’ (Ex.4:16).

In that sense, God was a ‘head’ (speaker of words) to Moses, and Moses was a ‘head’ (speaker of words) to Aaron. So of course in 1 Corinthians 11:3, God the Father is the ‘head’ of Christ, in the sense of being the invisible supplier of words to the visible Son. In Paul’s usage here, ‘head’ as an analogy drawn from the body is based on the pattern by which God spoke things into being (Gen.1), and worked by speaking through men and women who then became ‘prophets’ (Am.3:7). ‘Head’ in the sense of leadership is also drawn from God’s speech-acts through those people. For instance, the ‘heads’ (leaders) of Israel were to speak in various ways to the people: judge, instruct, and prophecy (Mic.3:9 – 11). Those leaders clearly include women like Miriam (Ex.15ff.), Deborah (Jdg.4 – 5), Isaiah’s prophetess wife (Isa.8:3), Huldah (2 Ki.24:14), and Noadiah (Neh.6:14), showing that men did not have a monopoly on leadership in Israel. Why would they in the church?[12] There is a chronological sequence of communication which we confess as a matter of salvation history, to be sure, but that is different from an ongoing hierarchy of power.

In fact, in 1 Corinthians 11:2 – 16, Paul reasons explicitly from the creation order in Genesis – a very underappreciated point – and thereby says women have the authority to pray (represent the community to God) and prophecy (preach and teach the word of the Lord) in the congregation. ‘Headship’ therefore indicates Christ sharing his authority to communicate God’s word with ‘man’ as male and female (aner as inclusive of women), a responsibility which God in creation shared with Adam first and Eve second, but with a view to developing their shared authority in marital oneness. That view is affirmed by the equal authority that the book of Proverbs gives to fathers and mothers over their children, right at the start of the book (Pr.1:8).

The translational ambiguity of aner and gyne in 1 Corinthians 11 now works in favor of women in church leadership. Since Paul is surely saying that ‘the husband is the head of a wife’ (note the singular article and pronoun, by which husband-wife is indicated, as it is unwarranted to say that a single man is categorically the head of ‘a woman’) in 11:3, then it is significant that he puts no further qualifications on women praying and prophesying. He simply encourages it. In Paul’s view, can a wife exercise speaking authority when her husband is sitting in the congregation? Yes. Can a daughter can do so with her father? Yes (a very underappreciated point!). Can a dishonored woman like an ex-prostitute, who by Roman law had to wear her hair uncovered and bound without the traditional Roman palla of honorable Roman women, do so with people of honored social and legal backgrounds? Yes, as Paul said that hair was sufficient for a woman’s ‘covering.’[13] There is no conflict of interest or violation of some supposed theological hierarchy of power, or even cultural decorum. Patton would probably have some difficulty incorporating the implications of 1 Corinthians 11:2 – 16 into his view of hierarchical and gendered authority. Paul’s creation theology and his reading of Genesis remain quite refreshingly different than Patton’s complementarian, hierarchical position. Like I said above, Paul, when he uses the term ‘head,’ has in mind a sequence of communication, which must be respected in a confessional way, but not a hierarchy of power. That sequence of communication leads to shared authority. For God has authority in His word, and shares it. The human ‘head’ per se does not have authority.

And, to put a sharp point to Patton’s balloon, the New Testament authors never use the Trinity as a model for political power, or the relationship between ruler and ruled (Rom.13:1 – 7; 1 Pet.13 – 17; cf. Lk.22:24 – 26), or even the relationship between church leaders and the general congregation (e.g. 1 Cor.9:1 – 18). Patton is attempting to go behind and under the text of the New Testament, offering us a foundation which he apparently thinks is missing. In effect, he claims to be explaining the apostles’ thoughts more clearly than they did.

Second, even for those Christians who agree with Patton, does this ‘Trinity as a hierarchy of power’ answer all the relevant questions for human society? Bear in mind that the Trinity is confessed by the great councils to be one in being (First Council, Nicaea, 325 AD), even one in mind and will (Sixth Council, Constantinople III, 680 – 681 AD), and one in majesty and power and activity (Athanasian Creed, 5th – 6th centuries), and who do not have a physical, embodied relationship with one another. How do we, as human beings, handle among ourselves questions of different perceptions and wills, having responsibilities which may be shared with, overlapping with, or totally distinct from the responsibilities of another, fault-finding and blame-affixing, delivering appropriate consequences, whether those consequences should be defined in a restorative or retributive framework, pondering solitary confinement, and so on? Can we derive clear answers to these human questions by thinking about the divine persons of the Trinity?

This brings us back immediately to the atonement. For the only ‘moment’ in the life of the Trinity that can possibly serve as a model is the death of Jesus, if and only if penal substitution is true. (See this post about why PSA advocates misinterpret Jesus’ quotation of Psalm 22 at the cross and this post about why the Father-Son relationship is not a hierarchy of power, according to Athanasius of Alexandria). If the crucified Son absorbed the infinite retributive justice of a God who is a hierarchy of power and authority, then we have all the pieces in place: a divine model of hierarchy that potentially validates all human hierarchy as stretching back into the Genesis creation order; a frame for legalistic, contractual obligations; and a retributive model of punishment for those who break that social order.

Oh.

Are you seeing it now? Your eyes should widen here as the lights go on.

These two doctrines alone fit well into the gaping holes which Enlightenment philosophers never filled. How is the individualistic person actually related to others, say, in a modern nation-state with different levels of power? What justifies the modern nation-state anyway? This version of evangelical Christianity seems to provide the answers. The doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement and the doctrine of the power-hierarchical Trinity offer, tantalizingly, the missing ingredients for Western society, which still feels ever so fragile. And once you have a divinely-sanctioned social order, who will serve as the Girardian scapegoat (the ‘ugly victim’) to maintain it? The violators, of course. In Patton’s view, that includes gender egalitarians.

Mistake #2 of Modern Evangelicals: Reconstructing the Sinai Covenant

Here is the second example of evangelicals endangering themselves and others by building an erroneous social order. The late Rousas John Rushdoony (pictured left, John Calvin pictured right – do they look alike, too?) and his Calvinist colleagues Greg Bahnsen, Gary North, and John Frame support the idea of ‘Dominionism’ or ‘Christian Reconstruction’ or ‘theonomy.’ Their influence on the Christian right is hard to measure, but it is thought to be quite substantial. Evangelicals Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell had publicly praised this work.[14] Journalists have labeled Ted Cruz a ‘Dominionist.’[15]

What does this position entail? Rushdoony, in his book Institutes of Biblical Law, supported the reinstatement of the ‘civic’ portion of the Mosaic Law, arguing for its full applicability. For example, he advocated carrying out the death penalty for homosexuality, adultery, incest, lying about one’s virginity, bestiality, witchcraft, idolatry, public blasphemy against the Christian God, false prophesying, kidnapping, rape, bearing false witness in a capital case, and even apostasy from Christian faith.[16] Interestingly enough, in February 2016, the Michigan State Senate renewed a law which says that oral and anal sex are criminal offenses punishable by fifteen years in prison. Since this law was renewed because it has an anti-bestiality clause, the law’s renewal admits of a kinder interpretation of Michigan lawmakers. However, Michigan is one of more than twelve states which still have anti-sodomy laws theoretically in effect, clearly intended to aggrandize the gay community, even though the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2003 ruling in Lawrence v. Texas declared all such laws unconstitutional.[17]

This position is more akin to Augustine’s imbalanced approach to political power than Constantine’s. Constantine and most of his heirs, for about 150 years, used political power to defend human rights in general. They were guided by Christian convictions about universal human dignity and what constituted ‘other-harm,’ which is always informed by religious convictions. Key Roman legislation influenced by Christians includes:

Ending the branding on the face of criminals condemned to the mines or the arena, ‘so that the face, which has been made in the likeness of celestial beauty, may not be disfigured’ (315 AD);[18]

Banning kidnapping and forced enslavement (315 AD);

Banning the breaking up of enslaved families (318 AD);

Declaring infanticide to be a crime (318 AD);

Legalizing the manumission of slaves before a Christian bishop, and granting them immediate Roman citizenship (318 AD);[19]

Making the voluntary killing of a slave/servant a capital crime (319 AD);[20]

Giving childraising assistance to impoverished parents in famines (322 AD, 329 AD);[21]

Ending the gladiator games (Constantine, date unknown;[22] 399 AD, 404 AD, 438 AD);

Restricting a husband’s right to divorce his wife (Constantine, date unknown);[23]

Granting a wife protection from her husband: to divorce, have child custody, and keep property (Justinian/Theodora 527 – 565 AD);[24]

Criminalizing the soliciting of prostitutes (the male customers), but not the woman prostituting herself.[25]

This last point is a helpful detail for my purpose here. Paul called consensual sexual sin self-harm (1 Cor.6:18). This categorization seems to have informed the position of the Christian theologians regarding female prostitution. They did not pass legislation against adultery and otherwise consensual sex between adults. Christians also recognized that the woman might not be entirely at fault for being a prostitute (due to debt, force, kidnapping, etc.), whereas the male customer was fully responsible for his act and contributed to a vast social problem, so they encouraged the state to prosecute the male customer – a fairly ‘enlightened’ and ‘progressive’ position indeed. This comports with a straightforward reading of Genesis 9:5 – 6 and Romans 13:1 – 7 that public policy should criminalize other-harm, not self-harm.

Constantine’s manner of administration also stressed peaceful political pluralism:

‘More significant even than his tolerance of pagan temples, Constantine continued to appoint pagans to the very highest positions, including those of consul and prefect, especially if we may assume that most whose religious affiliation is unknown were, in fact, pagans… But the most recent historians now regard Constantine’s conversion as genuine and cite the persistence of pagan elements in his reign as examples of his commitment to religious harmony…Of critical importance are two edicts [the Edict to the Palestinians and the Edict to the Eastern Provincials] issued by Constantine soon after he defeated Licinius to reunite the empire. Both stressed peaceful pluralism.

‘In both word and deed Constantine supported religious pluralism, even while making his own commitment to Christianity explicit. Thus, during Constantine’s reign, “friendships between Christian bishops and pagan grandees” were well-known, and the many examples of the “peaceful intermingling of pagan and Christian thought may…be thought of as proof of the success of [Constantine’s]…policy” of consensus and pluralism. This policy was continued by “the refusal of his successors for almost fifty years to take any but token steps against pagan practices.” And a public culture emerged that mixed Christian and pagan elements in ways that seem remarkable, given the traditional accounts of unrelenting repression.’[26]

But Augustine believed the church should go further and use the state’s political might to persecute heretics – in his case the Donatists – thereby turning heresy into a civil or criminal offense.[27] Augustine erased a line once held dear by prior theologians. Augustine’s predecessors in Roman North Africa, Tertullian and Lactantius, had said:

‘It is a fundamental human right, a privilege of nature, that every man should worship according to his own convictions: one man’s religion neither harms nor helps another man. It is assuredly no part of religion—to which free will and not force should lead us.’[28]

‘If you wish to defend religion by bloodshed, and by tortures, and by guilt, it will no longer be defended, but will be polluted and profaned. For nothing is so much a matter of free-will as religion; in which, if the mind of the worshipper is disinclined to it, religion is at once taken away, and ceases to exist.’[29]

Augustine’s mistake was taken as a positive move by the magisterial Reformers, who used political power to make state-churches. Luther did so in Germany, as did Zwingli in Zurich, Calvin in Geneva, Gustavus Vasa in Sweden, Henry VIII in England, and Knox in Scotland.

Calvin’s theology itself opened up a theological and hermeneutical danger to its adherents. Whereas Luther said that the Mosaic Law points us to Christ for our justification, Calvin added that Christ sends us back to the Mosaic Law for our sanctification. And whereas Luther treated the Mosaic Law as a unity, Calvin parsed it into three – moral, civil, and ceremonial – and argued that Christ abolished the ceremonial law. This left the Reformed tradition with the moral and civil dimensions of the Mosaic Law from Sinai to apply to their new contexts.[30] Their stress on a ‘law-gospel’ dialectic invited them to make this identification, as Reformed Protestants saw themselves as participating in two realities at once: the New Testament which speaks of not living under the Law, and yet also living by the Sinai covenant’s model in some sense. The Sinai covenant in Old Testament Israel specified death to witches (Ex.22:18), false prophets (Dt.13:5), idolaters (Dt.17:17), those who commit premarital sex (Dt.22:21) and adultery (Lev.20:10; Dt.22:22 – 24) and incest (Lev.20:11 – 14). In other words, it criminalized religious and sexual self-harm. Calvin turned the city-state of Geneva into a theocracy, drove out dissenters, and executed Michael Servetus at the stake for denying the Trinity. So the origins of political Calvinism ought to concern us. Adopting the framework leads one to want to reproduce the origin.

Whether the Mosaic Law can be apportioned into three parts is itself highly questionable,[31] for the family-land inheritance practices of Israel, which guided its familial, economic, and ecological vision (e.g. Leviticus 25, Numbers 30, 36), are quite fundamental to both ‘moral’ and ‘civil’ sections. Nor can that family-land system simply be duplicated straightforwardly, primarily because in the text of Scripture, the land is quite specific to Israel. And the church cannot lift the punitive portions of the Mosaic Law off the page and implement them in a straightforward fashion. Jesus and Paul taught believers to excommunicate but not kill those who persist in unrepentant sin (Matthew 18:15 – 20; John 8:1 – 11; 1 Corinthians 5:1 – 13). Paul’s handling of the Corinthian incest case, in particular, shows that he did not invoke the death sentence for the same crime in Leviticus 20:11 under the Sinai covenant. This is indicative that while the church might influence the state, the church is not a state.

However, the Calvinist English Puritans in Massachusetts and the Afrikaner Calvinist Boers in South Africa went further. They not only took the Sinai covenant as a political inspiration for a state; they read themselves into Israel’s story. They interpreted themselves as a covenanted ‘new Israel.’ Evangelical historian Mark Noll says:

‘The colonies’ main theological traditions were Reformed Protestant. Its most visible, influential, well-articulated, and enduring monument was the covenant Calvinism of Puritan New England.’[32]

Of course, there were superficial sociological similiarities to Israel coming out of Egypt which made that association poetic: fleeing persecution, crossing a body of water, finding a new land, encountering natives, and wanting to displace them and claim that land.

But sociology – or the outward similarity of circumstance – wasn’t the only factor, or even the main factor. There was an internal hermeneutical logic driving them to associate with Israel under the Sinai covenant. They were living out their understanding of the relationship between the Old and New Testaments, between ‘law’ and ‘gospel.’ Calvinist biblical hermeneutics made it possible for certain Calvinist groups to read themselves ‘into’ the story of Israel, as if they were a new chosen people living on a divinely-given land. Augustine’s willingness to use the state’s military power – though Augustine, to his credit, did not endorse killing – was amplified by the Reformers’ use of the Sinai covenant.

Granted, the political attitudes of present-day Calvinist-leaning evangelicals might be based on circumstance or other factors rather than interpretive method. Nevertheless, Calvin’s heritage leaves some open to the pull of supposed rational consistency, others to authoritarianism, and still others to both. These evangelicals can only look back to Calvin’s political work in Geneva as a successful model. Needless to say, this should alarm us. What should also alarm us is the fact that penal substitutionary atonement can not only sit on top of that framework very comfortably, the penal theory even originated from it. Effectively, the creation theology of Reformed theonomists (Zwingli, Calvin, Knox) involves politically imposing some replica of the Sinai covenant on each Gentile nation. The high federal Calvinist view that creation would eventually be sorted into the redeemed and the damned was accelerated into the present day: creation would be sorted into law-abiders and law-breakers.

Ironically, and further undermining their claims, is the fact that Reformed evangelicals filter the Sinai covenant through Enlightenment philosophy and Western capitalism. Which leads us to common mistake #3.

Mistake #3 of Modern Evangelicals: Modern Capitalism is God’s Will

On October 20, 2015, John Piper (pictured right), a Reformed Baptist theologian and prominent penal substitution advocate, who looks a bit like John Locke (pictured left; discussed below – and another eerie resemblance?) wrote an article against Bernie Sanders and ‘socialism.’ He admitted he knows little about economics and politics:

‘Well, I suppose I should put all of my misgivings up front to say I am not an expert in political science or economics. So take it for what it’s worth.’[33]

One wonders, then, why he believed himself qualified to write the article in the first place, or why he felt compelled to give his opinion at this timely juncture in the midst of a presidential election. Nevertheless, despite his lack of training in these subjects, Piper hones in on the supposedly biblical preeminence of private property and absolutely uncoerced giving, and concludes that capitalism is superior to socialism:

‘Socialism borrows the compassionate aims of Christianity in meeting people’s needs while rejecting the Christian expectation that this compassion not be coerced or forced. Socialism, therefore, gets its attractiveness at certain points in history where people are drawn to the entitlements that Socialism brings, and where people are ignorant or forgetful of the coercion and the force required to implement it — and whether or not that coercion might, in fact, backfire and result in greater poverty or drab uniformity or, worse, the abuse of the coercion as we saw in the murderous states like USSR and Cambodia.’[34]

Piper’s article is a good example of how evangelicals enshrine the principle of meritocratic-retributive justice in economics. He mistakes Israel’s land tenancy for land ownership. In Leviticus 25, every fifty years, God established His right to redistribute land back to Israel’s original family inheritance boundaries. God’s stated reason annulled any Israelite’s claim to private land ownership.

‘The land, moreover, shall not be sold permanently, for the land is Mine; for you are but aliens and sojourners with Me’ (Lev.25:23).

This rather large omission causes many evangelicals to miss the fact that God prevented Israelites from passing down advantage or disadvantage to their children and grandchildren. God ensured a baseline level of wealth and work, as land was both.

Not only that, God placed a human rights agenda high above the prerogatives of capital. He limited the libertarian economic freedom of the wealthy by preventing them from making loans with interest (Ex.22:26 – 27; Lev.25:35 – 38, Dt.23:19), especially to the poor. Usury is seen as extortion, a taking advantage of another person’s misfortune. It was deemed inappropriate as measured against the type of relationship God envisioned for human beings, which involved compassion, generosity, and hospitality. Hence it violated God’s relational vision and restorative principle of justice.

Also, God prevented debts from being transferred from one person to another, as a commodity (Lev.25:42). Debt in Israel was seen as a personal investment of trust, and perhaps risk as well, between two unique people. The debt could not be transferred to another without doing violence to the initial relationship. Hence debt could not be a publicly traded commodity. It could not be bought and sold. This is quite different from our modern view of economic relationships, where debts can be bought and sold.

On top of all that, God freed people from indebtedness within seven years (Dt.15:1) and/or on the fiftieth jubilee year (Lev.25:10, 47 – 55), whichever happened first. God compared indebtedness to enslavement. He likened releasing people from indebtedness to God releasing Israel from bondage in Egypt (Lev.25:55). Indebtedness was the leading cause of servitude and/or enslavement in the ancient world, and it is impossible for any informed reader of the Old Testament to miss the significance of God’s limitation on the power of capital. Where is this in Piper’s assessment? His implicit endorsement of financialized capitalism, which arrogates enormous power to banks and credit-debt contracts, is deeply problematic.[35]

Not only that, Piper misunderstands Bernie Sanders’ definition of ‘socialism.’ ‘Communism’ per se is the complete public ownership of material goods and the means of production. ‘Socialism’ is simply the administration of specific public goods like infrastructure, health care insurance, and education in such a way that reflects shared investment in shared goods (like roads) or in people (like our mental and physical health, level of education and job preparedness). If we place human rights ahead of property rights, this is only logical. But, strangely, Piper does not consider human rights. Therefore, he interprets taxes and public agencies, then, as completely coercive.

Special mention should be made of ‘libertarian socialism,’ which is the ownership of the means of production by labor. That is, in worker-owned corporations, laborers are personally invested in, and responsible for, the products and processes they deploy. Public intellectuals ranging from Ron Paul to Noam Chomsky support the worker-owned corporation. Today, by contrast, we have shareholder-owned corporations, where no one is personally invested in, or is institutionally responsible for, quality products and labor conditions. Shareholders are only liable for harmful products or bad work processes up to the point of their stock investment. Workers, in this system, are interchangeable and might be legally responsible for known negligence and abuse, but can work for the firm for short-term gain as well. In other words, the modern ‘limited-liability corporation’ becomes a legal fiction out of which both workers and shareholders have the incentive to extract their short term financial gain.[36] This is why modern corporations pollute the environment, produce harmful products, have unsafe work conditions, market directly to children, and so on.

Adam Smith, the notable economist held up by political conservatives as being for laissez-faire capitalism, actually stood against our modern form of capitalism, explicitly:

‘Smith, indeed, predicted what might happen in the Wealth of Nations, when he supported the idea of private companies (or copartneries) against joint stock companies, the equivalent of today’s limited liability firm. In the former, Smith said, each partner was “bound for the debts contracted by the company to the whole extent of his fortune”, a potential liability that tended to concentrate the mind. In joint stock companies, Smith said, shareholders tended to know little about the running of the company, raked off a half-yearly dividend and, if things went wrong, stood only to lose the value of their shares.

‘“This total exemption from trouble and from risk, beyond a limited sum, encourages many people to become adventurers in joint stock companies who would, upon no account, hazard their own fortunes in any private copartnery. The directors of such companies, however, being the managers rather of other people’s money than their own, it cannot well be expected that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private copartnery frequently watch over their own.”

‘The counter argument is that limited liability and the equity-financed model of the firm it has encouraged have been the bedrock of industrial capitalism. Without them, so it is said, there would never have been the rapid economic growth of the past two centuries. Smith would have had little time for this argument; his view was that a society should not exempt some people from the general laws of the land simply because their business may do well as a result.’[37]

But again, lying behind the view of Piper and other evangelicals, in their support of ‘capitalism’ of all forms, is a creation theology. In this case, it is the creation theology of John Locke. Locke was the political philosopher whose thoughts about property, the proper role of government in protecting property, and human nature, were foundational to the American Revolution. In his Two Treatises of Government, Locke interpreted the Genesis creation account by equating a person’s capacity to own ‘private property’ – in this case, land – with his claim to be industrious with it:

‘God gave the world to men in common; but since he gave it them for their benefit, and the greatest conveniences of life they were capable to draw from it, it cannot be supposed he meant it should always remain common and uncultivated. He gave it to the use of the industrious and rational, (and labour was to be his title to it;) not to the fancy or covetousness of the quarrelsome and contentious… God, by commanding to subdue, gave authority so far to appropriate: and the condition of human life, which requires labor and materials to work on, necessarily introduces private possessions.’[38]

Locke’s account of creation is defective for many reasons. First, he fails to consider the character of God in sharing land and all material resources with humanity. So he likewise fails to assign the values of generosity and hospitality to the image of God in which human beings were made. Essentially, Locke did not believe that human beings have a fundamentally relational obligation to one another – namely material and economic support – by which the use of creation becomes a medium of compassion and generosity, not acquisition. Where is Gregory of Nyssa’s conviction that every human being was to share in the wealth of creation? Locke’s error is related to the fact that he was not an orthodox Trinitarian theologian who prioritized genuinely Christian relational ethics; he was a rationalist making use of biblical language in support of his political ideas.

Second, Locke defined ‘rational’ in such a way as to call ‘irrational’ the Native American, whom he labeled ‘the Indian.’ Skim Locke’s Second Treatise of Government and you’ll see that he was quite aware of the Native American practice of not claiming land as private property. Intellectually, it was a thorn in his side, because he had to introduce another factor which justified white European practices of private property. Thus Locke’s use of the term ‘rational.’ This reinforced the cultural self-perception of the English, not least the Puritans, as being ‘rational,’ while the Native Americans were ‘irrational.’

But, once unlimited ‘private’ land ownership was read straight out of the Genesis creation account, and ‘capitalism’ was more or less established as God’s will for the creation, the reward-punishment principle (meritocratic-retributive justice) was applied to economic life. The colonies and the American founding fathers followed Locke.

Now I fully acknowledge there is a secondary or tertiary place for the meritocratic-retributive principle in Scripture (Prov.10:4; 2 Th.3:10 – 12). But Scripture does not make it the foremost principle in all relationships. For an Israelite to work land (Prov.10:4), he or she needs land to work, which is provided by the family-land inheritance and maintained by the jubilee (Lev.25). If we can extract any principle from Israel’s legislation, it is that meritocratic-retributive justice (reward for working, penalty for not working) can only be fully valid when the requirements of need-based distributive justice (supply of land and work) are met. Similarly, for a Christian to be able to work but choose not to, because s/he believes the return of Jesus is imminent (2 Th.3:10 – 12) is ridiculous. That person is not to be supported economically by the church, as Paul says. For s/he is able to work to be self-supporting and to give to others (Eph.4:28). But addressing structural injustice and providing for the poor in general is still an imperative (Lk.3:7 – 14; 12:13 – 34; 19:1 – 10; 2 Cor.8 – 9).

Sadly, evangelicals have been trained by John Locke (a heretic) to interpret raw, modern capitalism as a divinely inspired order from creation. This interacts with the penal substitution atonement theory, with its underlying principle of meritocratic-retributive justice. In a capitalist economy, people have to work and merit whatever they earn. But when the poor are ground down by the system, or when the global climate crisis is impending, evangelicals have to give some explanation for that which protects the system as still being divinely given. Evangelical bestselling author Wayne Grudem, in his 2010 book Politics According to the Bible, denies human-caused climate change and its significance:

‘Therefore, should we believe these predictions of dangerous results that will come from increased temperatures? I don’t think so.’[39]

Disappointingly, fellow evangelicals J.I. Packer, Chuck Colson, and Marvin Olasky apparently share his sentiment, based on their endorsements of his book. I critique Grudem’s view of economics in this earlier post.

So the explanations we are observing in some evangelical circles, that the poor are lazy and that climate change is not real, attest to evangelicals embracing capitalism in a mythological sense. ‘If the poor are poor, it must be because they are lazy.’ Since laziness is a moral violation of the capitalist order, we can see that the retributive principle is at work, not in a criminal justice framework, but in an economic framework. And of course, if black people, for instance, are perceived to be poor, then some white evangelicals (in particular) will feel the need to scapegoat them rather than the system or their support for it. For instance, evangelicals produce ‘the myth of black laziness’ (to replace ‘the myth of black criminality’) or ‘the dysfunction of the black family’ to scapegoat lower-income black people for ‘failing’ at capitalism.

[Added May 12, 2018: For example, in mid-2017, the Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Foundation conducted a study of over 1,686 Americans. They found that evangelicals – especially white evangelicals – are more likely than the general population to look at a person in poverty and blame the person for not trying hard enough to get out of poverty. The Washington Post notes:

When comparing demographics and religious factors, the odds of Christians saying poverty was caused by a lack of effort were 2.2 times that of non-Christians. Compared to those with no religion, the odds of white evangelicals saying a lack of effort causes poverty were 3.2 to 1.

The liberal-progressive Salon more aggressively criticizes Christians:

Its results showed that 46 percent of all Christians and 53 percent of white evangelicals said that “lack of effort” was “generally to blame” for the economic condition of poor people. Americans who were atheist, agnostic or had no religious affiliation, on the other hand, overwhelmingly said that “difficult circumstances” were more to blame for a person’s poverty, by a margin of 65 percent to 31 percent.

There is overwhelming evidence that people in poverty are affected by childhood trauma, past and present housing discrimination, predatory real estate evictions, the draining away of public services like schools and libraries (often with racial motivations), a credit system that preys on the poor and less financially literate, worse health due to pollution and toxins being placed next to poorer neighborhoods (also often with racial motivations), psychological trauma and stress due to poverty itself (see this and this). It behooves evangelical Christians to consider these and other factors. But again, evangelicals who are informed by penal substitutionary atonement bring in a framework of meritocratic-retributive justice as a divine principle, which places them at a disadvantage when looking at complex relationships.]

Is Penal Substitution a Gateway Drug?

In the second post in this series, I expressed concern about the church planting efforts of the Southern Baptist Convention and the Presbyterian Church of America. It bears repeating here. Because these denominations are strongly linked to the old Confederacy and slavery, they have a lot of money based on slavery and segregation which they now deploy as vocal advocates of penal substitution. So the question I’m pressing here is this: Is penal substitution a gateway drug? Not necessarily back to the days of slavery and segregation, but to right-wing political extremism and, as I explored in the third post, an ethic of infinite retribution, demonstrated by a willingness to lynch and torture’the other’?

Consider: Do certain ideas attract each other? Is this not just a coincidence of accidental errors? Why is there is an affinity among the SBC and PCA for views like ‘the Trinity is a hierarchy of power’ and ‘Reformed dominion and theonomy’ and ‘modern capitalism is God-given’? I believe some ideas have a magnetic attraction to certain other ideas.

I believe penal substitutionary atonement is a gateway drug. It is a magnet for bad creation theology, in which creation (humanity) needs to be sorted into two categories, according to the divine will and human institutions. It is also a magnet for regrettable and arbitrary readings of the Sinai covenant. Why does penal substitution do this? Because it seeks for itself compatible puzzle pieces to support and reinforce it. True, penal substitution can be treated as a standalone belief. Any point of doctrine can be treated that way. Yet because of the gravity of one’s doctrine of atonement, and because of its centrality in Christian thought and in biblical texts, penal substitution will exercise on all its supporters the strong tendency to define the will of God as dividing humanity into ‘redeemed’ and ‘damned’ from creation, to morally justify retributive punishment by sin and blame, and then to distinguish between the two categories of people, not just in eternity, but in actual human experience. I believe penal substitution supporters, even while well-intentioned, are doing the entire world a disservice. Enthusiasm for it in the U.S. continues to be a sign that, as with slavery, there is a pocket of European Christendom which resists authentic Christian discipleship.

I do respect the conservative stance that our desires mature with age so we shouldn’t be taken over by youthful, and especially sexual and materialistic, impulses. I also believe that healthy child-raising is a challenging, sacred task and is worthy of institutional support. However, I believe all children are worthy of investment, no matter what family they come from. I believe it is quite possible to be a fiscal conservative who believes in balanced budgets, and an economic progressive who believes that inequality is a sign of moral danger and an inherent problem in a democracy. I believe corruption in government can be reduced by a free press and public vigilance, and not just by shrinking its budget. I am troubled by the fact that we give massive corporations more ‘human rights’ than we do our future, unborn children. And I do not believe that meritocratic-retributive justice should be the highest principle of justice in public life. God is a God of restorative justice, who calls His entire creation forward, through redemption in Christ, to its glorification. So restorative justice needs to be higher.

In the next post, I’ll explain why penal substitution interferes with a proper understanding of the Sinai covenant. Back to biblical studies…

[1] Gregory of Nyssa, Fourth Homily on Ecclesiastes, specifically commenting on Ecclesiastes 2:7

[2] See my paper Slavery in the Bible, Slavery Today, http://nagasawafamily.org/article-slavery-in-the-bible.pdf

[3] See my paper Slavery in Christianity: First to Fifteenth Centuries, http://nagasawafamily.org/article-slavery-and-christianity-1st-to-15th-centuries.pdf

[4] E.g. Dr. Michael A.G. Haykin, et.al., ‘The First Abolitionist: Gregory of Nyssa on Slavery,’ The Andrew Fuller Center for Baptist Studies, June 18, 2013; http://www.andrewfullercenter.org/blog/2013/06/the-first-abolitionist-gregory-of-nyssa-on-slavery/.

[5] God even made clear, especially in Leviticus 25 with its jubilee economic and ecological vision which flows from the Genesis creation, that a whole range of other experiences are also not from the creation: having to take out a loan with an interest rate and therefore fall into crushing debt; having your creditor commodify your debt and sell your labor contract to another person; being permanently displaced from your family’s land; and being alienated from your family. Those things are from the fall, and meant to be undone by the jubilee year. God even prevented inequality of land ownership / tenantship to be passed down across the generations. After all, why should children inherit all the advantage or disadvantage their parents can give them? By pressing a ‘land reset button’ every fifty years, God provided His garden land to each new generation of Israelites, mirroring His gift of the garden of Eden to Adam and Eve. By participating in that, Israel’s adults, as a community, were enacting their ‘likeness to God’ towards their children as a community. All this is to say that, as we carefully consider the biblical narrative of creation, and the way that creation vision is understood by later biblical texts, Gregory of Nyssa’s stance against slavery on the basis of creation appears to be amply vindicated.

[6] Gregory of Nyssa, Sermon on Lent, 397 AD

[7] Gregory of Nyssa, Great Catechism chapter 15

[8] Augustine of Hippo, Confessions 1.18

[9] Oliver Ransford, The Great Trek (Great Britain: John Murray Publishing, 1972), p.11 – 12; Blake Williams, ‘Apartheid in South Africa: Is Calvin’s Legacy?’, University of Cumberlands, date unknown, https://www.ucumberlands.edu/downloads/academics/history/vol3/BlakeWilliams91.htm; P.J. (Flip) Buys, ‘Calvinism and Racism: A South African Perspective,’ World Reformed Fellowship, January 2009, http://wrfnet.org/resources/2009/01/calvinism-and-racism-south-african-perspective shows how the logic alone of high federal Calvinism could have been a resource for positive race relations. An excellent literature review as of 1980 was offered by Irving Hexham, ‘Christianity and Apartheid: An Introductory Bibliography,’ first published in The Reformed Journal, April 1980; republished in The Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, No. 32, September 1980; http://people.ucalgary.ca/~nurelweb/papers/irving/apart.html; but see my argument below.

[10] C. Michael Patton, ‘Why Jesus is Greater Than the Holy Spirit,’ Credo House blog, July 16, 2013; http://www.reclaimingthemind.org/blog/2013/07/why-jesus-is-greater-than-the-holy-spirit/

[11] The great Christian theologians and councils developed terminology to speak of the Trinity very slowly and guardedly. They expressed great reserve about the capacity of human language to speak with precision about the divine. They especially recognized that human language carries unwarranted human connotations drawn in from our finite and fallen experiences. Even something as basic as Father – Son language carries connotations of gender, temporality, differential power, and personal separation that need to be excised lest they cause irreparable damage to the broader theological tapestry. So the eagerness of this wing of the evangelical community to speak with such confidence about the inner relations of the Trinity is unnerving. For rebuttals to Patton, see Tony Jones, ‘Some (Honestly) Bad Reformed Theology Defending Hierarchies,’ Patheos blog, July 24, 2013, http://www.patheos.com/blogs/tonyjones/2013/07/24/some-honestly-bad-reformed-theology-defending-hierarchies/; Roger E. Olson, ‘Is There Hierarchy in the Trinity? A Series on a Contemporary Evangelical Controversy,’ Patheos blog, December 8, 2011, http://www.patheos.com/blogs/rogereolson/2011/12/is-there-hierarchy-in-the-trinity-a-series-on-a-contemporary-evangelical-controversy/

[12] Gordon Hugenberger, ‘Women in Church Office: Hermeneutics or Exegesis? A Survey of Approaches to 1 Tim 2:8 – 15,’ Journal of Evangelical Theology Society, September 1992; Gordon Hugenberger, ‘Women in Leadership,’ Park Street Church, April 14, 2008; http://www.parkstreet.org/teaching-training/articles/women-leadership

[13] See my notes on 1 Corinthians 11:2 – 16 here: http://nagasawafamily.org/paul_1corinthians.11.02-16.sg.pdf

[14] Adam C. English, ‘A Short Historical Sketch of the Christian Reconstruction Movement,’ in Derek Davis and Barry Hankins, editors, New Religious Movements and Religious Liberty in America (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2003)

[15] John Fea, ‘Ted Cruz’s Campaign Is Fueled By a Dominionist Vision for America,’ Religion News Service, February 4, 2016; http://www.religionnews.com/2016/02/04/ted-cruzs-campaign-fueled-dominionist-vision-america-commentary/

[16] Rousas John Rushdoony, Institutes of Biblical Law (The Craig Press, 1973)

[17] John Wright, ‘Michigan Senate Passes Bill Saying Sodomy Is A Felony Punishable By 15 Years in Prison,’ The New Civil Rights Movement, February 5, 2016; http://www.thenewcivilrightsmovement.com/johnwright/michigan_senate_passes_bill_saying_sodomy_is_a_felony

[18] Codex Theodosianus 9.40.2. Cf. Codex Justinianus 9.47.17

[19] Codex Theodosianus 4.7.1. Cf. Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History 1.9.

[20] Codex Theodosianus 9.12.1; cf. 9.40.1

[21] In 322 AD, Constantine declared,

‘If any parent should report that he has offspring which on account of poverty he is not able to rear, there shall be no delay in issuing food and clothing, since the rearing of a newborn infant will not allow any delay.’

He was probably inspired by the Roman church, who had been running a food network for 4000 (?) poor people. In 329 AD, Constantine declared,

‘Therefore if any such person should be found who is sustained by no substance of family fortune and who is supporting his children with suffering and difficulty, he shall be assisted through Our fisc before he becomes a prey to calamity.’

See O.M. Bakke, When Children Became People: The Birth of Childhood in Early Christianity (Grand Rapids, MI: Fortress Press, 2005), p.135

[22] Codex Theodosianus 15.12.1

[23] Codex Theodosianus 3.16.1

[24] James Allan Evans, The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002), p.17

[25] Leah Lydia Otis, Prostitution in Medieval Society: The History of an Urban Institution in Languedoc (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1985), p. 12 – 13 notes,

‘Prostitutes were supposed to register with the authorities; a state tax on these registered prostitutes was introduced in the first century A.D. A woman who had once registered as a prostitute retained that stigma for the rest of her life, even if she ceased all professional activity. Although the Church fathers fulminated against the commerce of the body with the same ferocity as against other sins of the flesh rampant in the Roman world, prostitution, being a social phenomenon rather than a personal sin (such as fornication), did not, strictly speaking, lie within the spiritual jurisdiction of the Church. Despite its condemnation of all premarital and extramarital sexual activity, the Church recognized prostitution to be an inevitable feature of worldly society, which it had no hope or ambition to reform. Saint Augustine even warned that the abolition of prostitution, were it possible, would have disastrous consequences for society; the practice, he believed, was a necessary evil in an inevitably imperfect world. Canonical wrath was focused, rather, on those who profited from this commerce, for, while prostitution was regarded as a social phenomenon distinct from the sin of fornication, procuring was considered by the Church to be synonymous with the sinful act of encouraging debauch (since the latter is usually associated with a pecuniary motive, whereas fornication can be committed out of passion as well as out of desire for money). Procuring was therefore considered to be a matter of spiritual jurisdiction, and strong measures were taken against it at the Council of Elvira (c. 300), whose canons were included in most of the major canon-law collections of the Middle Ages.’

[26] Rodney Stark, Cities of God: The Real Story of How Christianity Became an Urban Movement and Conquered Rome (Harper Collins: New York, 2006), p.189 – 194. See also Stark, The Triumph of Christianity (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2011), p.178 – 180

[27] Augustine of Hippo, A Treatise Concerning the Correction of the Donatists 14, 22 – 24 (circa 417 AD); http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf104.v.vi.i.html

[28] Tertullian of Carthage (c.155 – c.240 AD), To Scapula chapter 2

[29] Lactantius (c.250 – c.325 AD), Of the Divine Institutes book 5, chapter 20

[30] Greg Bahnsen, ‘The Reformed Theonomic Approach to Law and Gospel,’ in Wayne G. Strickland, editor, Five Views on Law and Gospel (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1993, 1996)

[31] Douglas Moo, ‘The Law of Christ as the Fulfillment of the Law of Moses: A Modified Lutheran View,’ in Wayne G. Strickland, editor, Five Views on Law and Gospel (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1993, 1996); see also his critique of Greg Bahnsen’s Reformed theonomic position

[32] Mark A. Noll, America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2002)

[33] John Piper, ‘How Should Christians Thinks About Socialism?’, Desiring God blog, October 20, 2015; http://www.desiringgod.org/interviews/how-should-christians-think-about-socialism; see also Wayne Grudem, Politics According to the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2010); see my critique of Grudem in Post 7 of Atonement & Ministry and also here: https://newhumanityinstitute.wordpress.com/2015/09/14/interpreting-jesus-and-atonement-practical-issue-7-atonement-gods-character-and-economic-justice-a-critique-of-wayne-grudem/.

[34] Ibid

[35] See my blog post critiquing Tim Keller and usury, in Post 8 of Atonement & Ministry and also here: https://newhumanityinstitute.wordpress.com/2015/09/22/interpreting-jesus-and-atonement-practical-issue-8-atonement-gods-character-and-economic-justice-a-critique-of-tim-keller/

[36] The limited liability corporation is ably critiqued by Paul Mills and Thomas Schluter, After Capitalism: Rethinking Economic Relationships (Cambridge, England: Jubilee Centre, 2012), ch.10

[37] Larry Elliott, ‘Plc: Prerogative of the Unaccountable Few: Adam Smith Argued for Free Trade and Self-Interest, But Not This Kind of Capitalism,’ The Guardian, July 9, 2007; http://www.theguardian.com/business/2007/jul/09/politics.economicpolicy;

[38] John Locke, Second Treatise of Government, edited by C.B. Macpherson (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 1980), p.21 – 22

[39] Wayne Grudem, Politics According to the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2010), p.367