Post 3: What Lynching, Torture & Scapegoating Have in Common: Penal Substitution

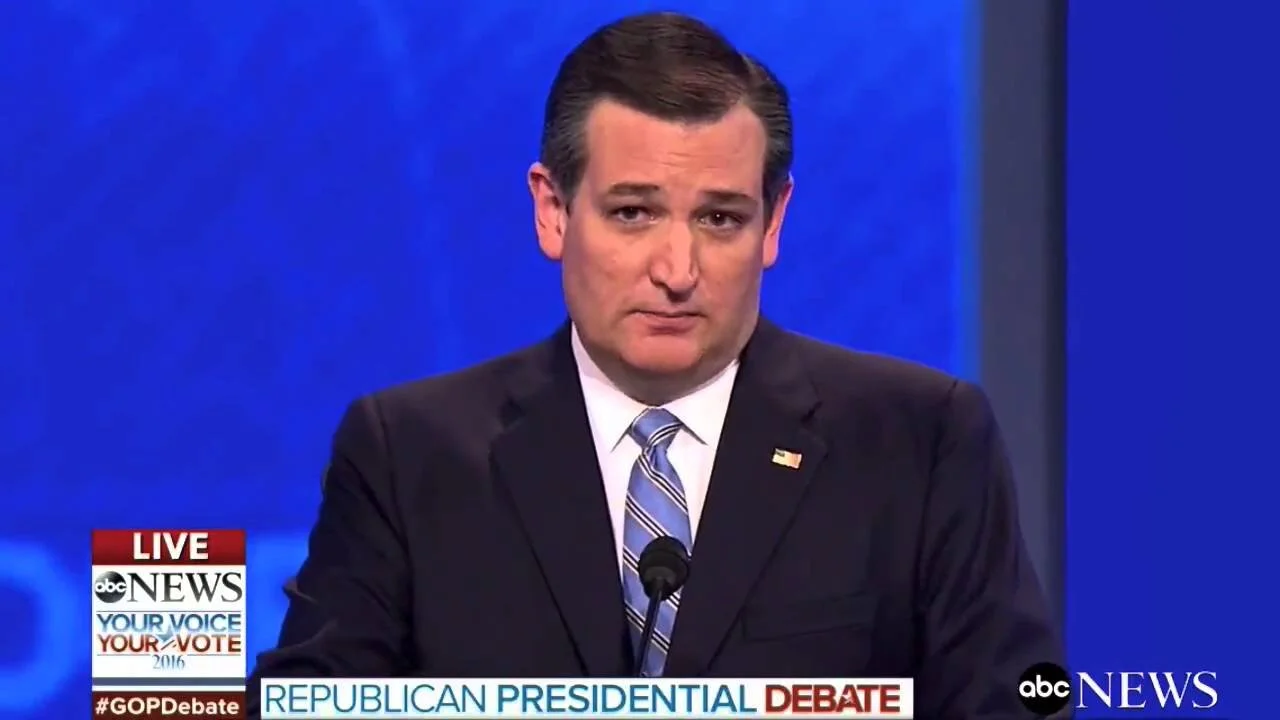

Ted Cruz as Example

Recently, Ted Cruz said he would carpetbomb ISIS,[1] and use waterboarding on a limited basis;[2] Donald Trump said he would wholeheartedly bring back waterboarding and worse, and called Ted Cruz ‘a pussy’ for being soft on waterboarding.[3] These Republican presidential candidates are not only applauded for these kinds of statements; they are the most heavily supported by evangelical American voters.

This is an important indicator that an ethic of retribution has been internalized by many white evangelicals. In the U.S., evangelicals already favor capital punishment more than the overall population.[4] What happens when treason or terrorism is at stake? Evangelicals call for even more punishment. Evangelicals are more likely than the general population to justify torture of terrorists or even suspected terrorists. When asked about the controversial CIA waterboarding treatment of men suspected of being terrorists and detained at Guantanamo Bay, 69% of white evangelicals believe it was justified; only 20% said it was not; that compares to 59% of the general population believing it was justified.[5]

Girard’s scapegoat theory helps explain why white evangelicals in particular have this reaction. Psychologically, the emotional distancing seems to harden so that ‘the other’ now becomes ‘the transgressive other.’ So the social order is maintained by scapegoating and blaming someone for being unacceptably evil.

Additionally, many American evangelicals believe in ‘American exceptionalism.’ They believe the Puritan myth that the U.S. is ‘God’s chosen nation’ in a sense akin to Israel in the Old Testament. So when ‘the other’ transgresses the entire social order, which is now vested with the divine will, what moderates the retributive punishment for that? My concern is that, in precisely those moments, the Protestant endorsement of retributive justice, cultivated by years of hearing the penal substitution atonement theory from the pulpit, emerges as rage. I believe penal substitution adherents have cultivated in America, inadvertently or not, an ethic of infinite retribution.

Lynching as the Precursor to Waterboarding

When we see evangelicals applauding Trump and Cruz, we should not be surprised to find that penal substitutionary atonement contributed to lynching. That may surprise some people who are not familiar with the studies on it. And some will question why I believe that story needs to be told. It’s because white evangelical Protestants tend to feel the same way towards treason or terrorism today as they did towards transgressions against the racial order under slavery and Jim Crow. These acts are perceived as high-handed crimes against an entire social order, not just particular individuals.

Need proof? Let’s start with a basic question. Does belief in penal substitution impact a Christian’s beliefs about criminal justice? Yes. British theologian Timothy Gorringe carefully examined church history from the eleventh to the nineteenth centuries to observe how atonement theology and criminal justice paradigms interacted with each other. In his assessment, in his 1996 book God’s Just Vengeance: Crime, Vengeance, and the Rhetoric of Salvation, the evidence is clear:

‘Wherever Calvinism spread, punitive sentencing follows.’[6]

And by ‘Calvinism,’ Gorringe especially means the penal substitutionary atonement theory. Moving into the American context, John Winthrop and the Massachusetts Bay Puritans, who were nurtured in this theology, found it only logical to model their criminal justice system on the principle of stern retributive justice, even against heresy:

‘Participation in a Puritan community was understood as an opportunity to serve God, and any act against that social order was considered a sin against God. For colonial authorities, sin and crime were indistinguishable. In an environment riddled with terror and violence, bloody conflict and sudden death, wars with indigenous tribes, and outbreaks of smallpox, people made sense of their daily lives in terms of sin and feared that God was punishing them. The commitment to creating an untainted, religious commonwealth resulted in the Puritans’ unforgiving response to any activity that was perceived to threaten that end.’[7]

Thus, the Massachusetts Puritans exiled ‘heretics’ and put to death four Quakers who refused to leave, simply for being Quakers. This posture goes back to Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430 AD), who was the first theologian to argue that the church should use the state to punish and persecute heretics.[8] This was a deeply regrettable combination. In the 1800s, American Protestant theology also envisioned the plantation as divinely authorized by God as the way He intended white men to rule the land.[9] So what system would they put in place to punish the criminal ‘other’? A punishment fit for perceived terrorists and traitors.

When white Protestants lynched black men (mostly, although black women and one Jewish man were also known to be lynched), they did so in part because they believed the myth of the black male rapist who threatened to sully the honor of white women and disturb the order of the white community.[10] Since the highest Christian vision of purity – the white woman – was ‘threatened’ by the black male transgressor, the act merited retribution of the highest order:

‘Nearly 25 percent of the lynchings of African Americans in the South were based on charges of sexual assault. The mere accusation of rape, even without an identification by the alleged victim, could arouse a lynch mob. The definition of black-on-white “rape” in the South required no allegation of force because white institutions, laws, and most white people rejected the idea that a white woman would willingly consent to sex with an African American man. In 1889, in Aberdeen, Mississippi, Keith Bowen allegedly tried to enter a room where three white women were sitting; though no further allegation was made against him, Mr. Bowen was lynched by the “entire (white) neighborhood” for his “offense.” General Lee, a black man, was lynched by a white mob in 1904 for merely knocking on the door of a white woman’s house in Reevesville, South Carolina; and in 1912, Thomas Miles was lynched for allegedly inviting a white woman to have a cold drink with him.’[11]

The angry community responses to as-yet unproven accusations are evidence that whites interpreted sexual boundary-crossing by black men not merely as a transgression against individual white women. They were violations of an entire social order, divinely instituted. So the whole community – especially fathers, brothers, other possible suitors, sons, and other male members of the community who felt some level of possessiveness over the bodies of their mothers, daughters, sisters, etc. – felt permission to be enraged. Consider this incident:

‘In his narrative of the lynching of Henry Smith—killed for the alleged rape and murder of 3-year-old Myrtle Vance—writer P.L. James recounted how the energy of an entire city and country was turned toward the apprehension of the demon who had devastated a home and polluted an innocent life. James wasn’t alone.’[12]

Entire white communities also lynched black people for trivial ‘offenses,’ like not using the word ‘sir’ when addressing a white man.[13] The black man served as the scapegoat in the Girardian sense for preserving the honor of white Christian society. The combination of categories – divinely given social order, female purity, retribution, vengeance, and so on – bespeak a theological vision, in this case a warped Protestant vision.

Hence, observers record their impressions of lynchings as having religious significance: white people gathered to watch black men be castrated, tortured, burned, and hung in the atmosphere of a religious ritual.[14] Indeed,

‘A major reason why lynching is connected to Christianity is that most lynchings actually occurred on Sunday afternoons, shortly after church services concluded.’[15]

How could white Christians go so far beyond the ‘eye for an eye’ proportionality principle in Jewish law? (As a side note, as I’ve noted in another post,[16] the ‘eye for an eye’ principle was established as an outer limit on a restorative justice process that, as stated in Exodus 21:22 and 30, allowed the victim to name a compensation price instead of calling for a strictly proportional punishment; ‘an eye for an eye’ was not an automatic legal principle in Jewish law, so those who interpret it thus are misinformed.) Because an entire social order was at stake. A social order that was ‘sacred.’ Notice the terms used here about a ‘sacred order’:

‘Many other defenders of lynching understood their acts as a Christian duty, consecrated as God’s will against racial transgression. “After Smith’s lynching,” [historian Amy Louise] Wood notes, “another defender wrote, ‘It was nothing but the vengeance of an outraged God, meted out to him, through the instrumentality of the people that caused the cremation.’” As UNC–Chapel Hill Professor Emeritus Donald G. Mathews writes in the Journal of Southern Religion, “Religion permeated communal lynching because the act occurred within the context of a sacred order designed to sustain holiness.” The “sacred order” was white supremacy and the “holiness” was white virtue.’[17]

Since most white Americans viewed black people as ‘other,’ the already retributive logic of Protestant atonement theology provided no intrinsic intellectual or moral barrier to lynching. Instead, evangelicals seem to have been shaped by the relationally distancing retributive psychology located within penal substitution. It encouraged whites to maintain their emotional distance from blacks and therefore punish them more severely. Again, I think the parallel to today would be the person accused of treason or terrorism. Historian Donald G. Mathews concludes his thorough study published in the year 2000, ‘The Southern Rite of Human Sacrifice: Lynching in the American South,’ by saying:

‘The cross symbolized a salvation effected by Christ’s paying just satisfaction for the sins of humanity: focus was on the justice of punishment. Even God had had to pay the price for human sin… Because the myth of God’s just vengeance permitted whites’ obsession with punishment to rule their relations with blacks there was no restriction within the core myth of Christian identity to the racism that clouded their vision. It was possible for the rare white Christian to sense that atonement demanded empathy with sacrificial victims so that there might be no more “victims”; but this insight remained hidden from most Southern whites for the moment… lynching was but one way of using death to solve problems of violence and justice.’[18]

How did white Protestants so easily place black people into the category of ‘other’? Fear of racial uprisings has been offered as an answer, but that mostly begs the question.

Augustine, Luther, and Calvin: The Other as the Sinner

Augustine of Hippo bears much responsibility for giving a Christian interpretation of ‘the other’ specifically as the sinner. It is important to understand that the penal substitution theory reposes on a larger theological framework of ‘double predestination’ attributed to Augustine. In some of his writings, Augustine said that God by grace draws some people to salvation, and not others.[19] This theory of ‘double predestination’ caused considerable controversy in Augustine’s own time.[20] It was not the teaching of the church during the previous five centuries, nor subsequent centuries in the Catholic and Orthodox traditions.[21] Prior Christian tradition understood God as giving grace to all, where God enabled human free will.[22] Yet Luther and Calvin embraced Augustine’s theory of double predestination,[23] reversing the theological concessions of Augustine’s own disciples, and reintroduced the sinner as ‘the other.’

Am I just trying to position theology as the main driver of history? I wish I were. Sociologist Kaia Stern observes that Augustine’s division of humanity into two categories had this recurring effect throughout Protestant history:

‘Augustine’s belief in the natural inequality of mankind and his notion of original sin [the notion that we inherit the personal guilt of Adam and Eve, and not just their corrupted nature in what the Eastern Orthodox call “ancestral sin”] have been applied to validate oppressive and dehumanizing institutions (like chattel slavery) in an effort to preserve “social order” and promote the “human good.” More significantly, his view of original sin, which was central to the religious worldview of Protestant colonial America, profoundly shaped US attitudes and policies toward crime and punishment.’[24]

The Augustinian doctrine of differential grace led to the suspicion that some human beings were, in a theological sense, sub-human. After all, those not graced by God were more likely to act sinfully and criminally. This ‘othering’ of the African person (and Native American person) accompanied colonialism.[25]

Luther and Calvin went farther than Augustine. They supplied an inner rationale for how God would judge those He damned: retributive justice. This new piece of the overall theological puzzle purported to answer not only the question of the basis on which God would punish the sinner infinitely, but also the question of why God needs to predestine some people to damnation. The Calvinist Westminster Confession of Faith, drawn up in 1646, says that heaven and hell show two opposing characteristics of God:

‘[Judgment] day is for the manifestation of the glory of His mercy, in the eternal salvation of the elect; and of His justice, in the damnation of the reprobate, who are wicked and disobedient.’[26]

John Piper, a modern advocate of high federal Calvinism and penal substitutionary atonement, explains Westminster in terms of God needing to express both of those attributes:

‘God created the universe so that the full range of His perfections – including wrath and power and judgment and justice – will be displayed…’[27]

For those unfamiliar with how penal substitution and double predestination fit together, here is a brief explanation. (1) God wants to pour out infinite retributive justice towards all, because each person has sinned against Him. (2) God has arranged for Jesus to absorb it for some, saving them from God’s wrath. (3) But God has predestined others to damnation beforehand because God needs to demonstrate ‘the full range of his perfections,’ as Piper says. (4) Since there must be some people to receive God’s blessing and others to receive His damnation, ‘double predestination’ must be true.

Hell was a fiery torture chamber where God demonstrated His punitive justice and humans feel the desire to escape. Retributive justice explained to Protestants why some people will be in hell, and what God will be doing to them: For if Jesus absorbed all of God’s retributive justice, there would logically be no hell, and some of God’s attributes would not be shown. The redeemed might even be less grateful, as Piper suggests.

‘Two effects happen that glorify God. One is that His grace, which is the apex of His glory, shines more brightly because it is against the backdrop of judgment and of sin. And we, the undeserving beneficiaries of this election and redemption are moved to a more exquisite joy and gratitude for our salvation because we’ve seen all the lostness of people who are no worse than we were and we no better than them. We should be in hell as well and our gratitude will be intensified. So at least those two senses are the answer to his question. How does God get glory? His grace and mercy shine more brightly against the darker backdrop of sin and judgment and wrath. Our worship and our experience of that grace intensifies and deepens because we see we don’t deserve to be where we are.’[28]

Therefore, God must sovereignly will to save only the elect so He can reveal all of Himself. Towards those predestined for salvation, He shows mercy, love, and grace. Towards those predestined for damnation, He shows wrath, vengeance, and infinite retributive justice.

In the perception of many observers, this vengeful, wrathful side of God informed the practice of lynching:

‘It is exceedingly doubtful if lynching could possibly exist under any other religion than Christianity,” wrote NAACP leader Walter White in 1929, “No person who is familiar with the Bible-beating, acrobatic, fanatical preachers of hell-fire in the South, and who has seen the orgies of emotion created by them, can doubt for a moment that dangerous passions are released which contribute to emotional instability and play a part in lynching.” And while some church leaders condemned the practice as contrary to the Gospel of Christ—“Religion and lynching; Christianity and crushing, burning and blessing, savagery and national sanity cannot go together in this country,” declared one 1904 editorial—the overwhelming consent of the white South confirmed White’s view.’[29]

The qualification I would make to the article above is to say that the doctrine of hell as a place where God’s retributive justice is meted out is distinctively Protestant. For Protestants, ‘hell-fire’ tends to be interpreted as a literal fire, and in its purpose expresses the infinite vengeance of God expressed on the bodies of sinners.

To be fair to Augustine, even he did not believe in this retributive framework. To Augustine, sin was an addictive corruption in the human being. So he held, along with all the early theologians, the ontological-medical substitution atonement,[30] and that hell was the result of disordered desires shaped by poor human choices. To him, hell was the ongoing commitment of a loving God to burn out of people what opposed His love. Hence, he said,

‘Every inordinate affection is its own punishment.’[31]

Since Jesus burned away the corruption and healed human nature in himself, offering himself to us by the Spirit, so hell was the experience of trying to rid yourself unsuccessfully of God’s purifying and intimate love.[32] Roman Catholics and Orthodox believers understand biblical texts about divine ‘fire’ in hell not as texts by themselves, but as part of an entire literary theme running through Scripture. Divine ‘fire’ corresponds with divine ‘light,’[33] and is purifying in its purpose. It is only painful in a secondary sense for those people who eternally resist God’s purification.[34] Compare Augustine’s mentor Ambrose of Milan’s exposition of fire in Scripture in his treatise On the Holy Spirit against Jonathan Edwards’ sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God[35] to see the vast difference. In Augustine’s mind, God does not ‘need’ for some people to become unbelievers. Yet for the Protestant Reformers, God did.

So, if God metes out infinite retribution in eternity, what prevents His followers from setting up political institutions which would imitate Him in a lower register? Is it not somewhat in keeping with imitating God to do so? The church may be the place where people experience mercy, but is not mercy made more meaningful when many other institutions express punitive judgment?

A Tragedy of Errors, or an Attractive Combination of Magnetic Ideas?

I know of objections people have already raised. Someone argue that an unjust and excessive punishment like lynching was a gross distortion of evangelical thought and not a true outworking of it. If penal substitution had been taught authentically, defenders might say, racism would not have been acceptable to begin with. For ‘all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God’ (Rom.3:23), so all people are equally sinners before God, and in need of Christ. Perhaps so. And of course, one can argue that there was a perfect storm here: White American evangelicals reconfigured key theological ideas in ways that were deeply but coincidentally unfortunate. (1) Augustine’s teaching about the church using the state to persecute heretics was mistaken. (2) His theory of differential and arbitrary grace, even if it were true as Lutherans and high federal Calvinists claim, does not map onto the racial distinction between white versus black people. (3) Luther’s and Calvin’s theory of penal atonement does not justify lynchings. And (4) the gross American Protestant mishandling of ‘slavery’ as embedded in nature and ‘the curse on Ham/Canaan’ in Scripture was outrageous and a tragedy of error. All this I grant. Indeed, each point above should be considered on its own intellectual merits, and not for the use it was put to by people who were in error.

But I also feel the objections – when parsed this way – miss the point. For Girard’s scapegoat psychology must be consulted for why the convergence of these theological positions was not, and is not, coincidental. We as fallen human beings seek a web of ideas like this. We are drawn to scapegoat others, just like Adam blamed Eve (‘this woman’) and God (‘You gave me’) for his own sin. If human communities regularly look for a scapegoat because of an intuition to blame, once we find one, how easily do we relinquish it? And how easily do we give up scapegoating altogether? Especially when evangelical exegetes and theologians reverse the meaning of the biblical scapegoat itself! That is, they take God’s expression of taking Israel’s impurity into Himself, and turn it into God assigning blame for violating His sacred order onto a sacrificial victim. They revert back to what Girard cautions us against. And a central litmus test is the interpretation of the scapegoat in Leviticus 16.

The major theological problem I wish to highlight here is this: In one sense, the doctrine of penal substitution can float completely free from a healthy and robust biblical doctrine of creation. Penal substitution only needs a minimalist doctrine of creation: that we exist. Conceptions of relational and legal duties, social order, and institutional realities of hierarchy can change all around the doctrine of penal substitution and even influence the way we see God’s purpose for His own commandments. This is actually dangerous. For penal substitution can be placed within a society that is wholly unjust and unbiblical because it has no inherent critique of such an order. All penal substitution refers to is a change in God, not a change in us, or in our relations, informal or institutional. Given that evangelicals accept torture at higher rates than the general population, I wonder if evangelicals are also less likely to believe in reports of police brutality?

But in another sense, the doctrine of penal substitution is a magnet for a very unhealthy doctrine of creation. Penal substitution fosters the view that creation was meant to be sorted. Because penal substitution provides a compelling theological reason to divide creation into two – the redeemed part and the damned part – and distinguish between them in lived human experience, people tend to produce that division along retributive justice lines. As Timothy Gorringe observed, ‘Wherever Calvinism spread, penal sentencing follows.’[36] People need to be sorted by using moral, if not legal, blame.

As I’ll show in the next post, early Christians became abolitionists because of the biblical doctrine of creation! They understood God to be restoring the whole creation to what He intended, and thus abolition was appropriate. Are we missing something as we read Genesis? More on that in the next post.

[1] Louis Jacobson, ‘Ted Cruz Misfires on Definition of ‘Carpet Bombing’ in GOP Debate,’ Politifact, December 16, 2015; http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2015/dec/16/ted-cruz/ted-cruz-misfires-definition-carpet-bombing-gop-de/; Pamela Engel, ‘Ted Cruz Doubles Down on Vow to ‘Carpet-Bomb’ ISIS,’ Business Insider, January 28, 2016; http://www.businessinsider.com/ted-cruz-isis-carpet-bomb-strategy-2016-1

[2] Nick Gass, ‘Cruz: Waterboarding is Not Torture,’ Politifact, February 6, 2016; http://www.politico.com/blogs/new-hampshire-primary-2016-live-updates/2016/02/ted-cruz-waterboarding-2016-debate-218879;

[3] Tessa Berenson, ‘Donald Trump Repeats Offensive Name for Ted Cruz at Rally,’ Time, February 8, 2016; http://time.com/4213231/donald-trump-ted-cruz-offensive-name/

[4] H. Prejean, Dead Man Walking: An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States (New York: Random House, 1993), p. 124.

[5] Sarah Posner, ‘Christians More Supportive of Torture Than Non-Religious Americans,’ Religion Dispatches, December 16, 2014; http://religiondispatches.org/christians-more-supportive-of-torture-than-non-religious-americans/; Pew Research Forum, The Religious Dimension of the Torture Debate, Pew Research Center, April 29, 2009; http://www.pewforum.org/2009/04/29/the-religious-dimensions-of-the-torture-debate/ makes the careful distinction based on behavior: Attend religious service at least weekly / monthly a few times a year / seldom or never. The percentage of people agreeing with the use of torture *increases* with the frequency of attending a religious service. See also Steve Benen, ‘This Week in God 12.20.14,’ The Rachel Maddow Show MSNBC, December 20, 2014; http://www.msnbc.com/rachel-maddow-show/week-god-122014

[6] Timothy J. Gorringe, God’s Just Vengeance: Crime, Vengeance, and the Rhetoric of Salvation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p.140, discussed by Christopher D. Marshall, Beyond Retribution: A New Testament Vision for Justice, Crime, and Punishment (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), p.60 and David G. Mathews, below.

[7] Kaia Stern, Voices from American Prisons: Hope, Education, and Healing (New York: Routledge, 2015), p.43

[8] Augustine of Hippo, A Treatise Concerning the Correction of the Donatists 14, 22 – 24 (circa 417 AD); http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf104.v.vi.i.html

[9] David Oshinsky, Worse than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice (New York, NY: Free Press Paperbacks, 1996), p.11

[10] Bill Moyers, ‘Black Men Were Burned Alive in the Bible Belt,’ Alternet, February 6, 2015; Campbell Robertson, ‘History of Lynchings in the South Documents Nearly 4,000 Names,’ New York Times, February 10, 2015; but compare to a map of all 50 states, where white Americans in non-Southern states carried out lynchings as well, though in smaller numbers: Library of Congress, Lynchings by State and Counties, 1900 – 1931: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3701e.ct002012/.

[11] Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, 2015, ;http://www.eji.org/files/EJI%20Lynching%20in%20America%20SUMMARY.pdf; for a poignant digest, see Rod Dreher, ‘When ISIS Ran the American South,’ The American Conservative, February 10, 2015; http://www.theamericanconservative.com/dreher/isis-american-south-lynching/

[12] Jamelle Bouie, ‘Christian Soldiers: The lynching and torture of blacks in the Jim Crow South weren’t just acts of racism. They were religious rituals.’ Slate, February 10, 2015; http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/politics/2015/02/jim_crow_south_s_lynching_of_blacks_and_christianity_the_terror_inflicted.html, emphasis mine; cf. Amy Louise Wood, Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890 – 1940 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2011)

[13] Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror

[14] Donald G. Mathews, ‘The Southern Rite of Human Sacrifice: Lynching in the American South,’ Journal of Southern Religion, August 22, 2000; http://jsr.fsu.edu/mathews.htm; note his very extensive bibliography and the works already done on this subject by scholars of religion; Paula J. Giddings, Ida: A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching (New York: Harper, 2009) is also particularly informative from a historical standpoint

[15] Dominique Gilliard, ‘Sunday Lynchings: The Church’s Role in Our Nation’s Racism,’ Convergence Oakland, February 27, 2013; http://convergeoakland.org/2013/02/sunday-lynchings-the-churchs-role-in-our-nations-legacy-of-racism/

[16] See Post 6 of the series on Atonement & Ministry, also found here: https://newhumanityinstitute.wordpress.com/2015/09/09/interpreting-jesus-and-atonement-practical-issue-6-is-retributive-justice-the-highest-form-of-justice-does-atonement-theology-impact-our-framework-for-criminal-justice/

[17] Jamelle Bouie, ‘Christian Soldiers’ Slate, February 10, 2015

[18] Donald G. Mathews, ‘The Southern Rite of Human Sacrifice: Lynching in the American South,’ Journal of Southern Religion, August 22, 2000; http://jsr.fsu.edu/mathews.htm

[19] For an excellent and sympathetic treatment of Augustine’s writings and the critical reception of his teaching, see Seraphim Rose, The Place of Blessed Augustine in the Orthodox Church (Platina, CA: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2007 third edition)

[20] Even during his life, Augustine’s teachings drew forth concerned responses from John Cassian and Vincent of Lerins, who were leaders of Christian monastic communities in Roman Gaul. See Angelo Di Bernardino, editor, Patrology IV: The Golden Age of Latin Patristic Literature From the Council of Nicea to the Council of Chalcedon (Allen, TX: Christian Classics, 1999) remarks, ‘His [Cassian’s] concepts of freedom, of original sin, and of anthropology are derived from Irenaeus of Lyons.’ C.f. Irenaeus (130 – 202 AD), Against Heresies, 4.37.1; 4.38.3.

[21] Seraphim Rose, The Place of Blessed Augustine in the Orthodox Church notes that after about a century of disturbance, these debates were thought to be sufficiently resolved by the fourteen bishops of the Council of Orange in 529 AD. Much scholarly effort has gone into demonstrating that Augustine was inconsistent in his own writings about God’s grace and human free will, and how Augustine’s writings were received by his fellow Christians. But that discussion is not what concerns us here.

[22] Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church Vol.III, (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdman’s Publishing,1867), ch.9, sec.146 writes,

‘The Greek, and particularly the Alexandrian fathers, in opposition to the dualism and fatalism of the Gnostic systems, which made evil a necessity of nature, laid great stress upon human freedom, and upon the indispensable cooperation of this freedom with divine grace; while the Latin fathers, especially Tertullian and Cyprian, Hilary and Ambrose, guided rather by their practical experience than by speculative principles, emphasized the hereditary sin and hereditary guilt of man, and the sovereignty of God’s grace, without, however, denying freedom and individual accountability.’

J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines (New York, NY: Harper One, 1978), p.352, 356 writes,

‘A point on which they (the Eastern Fathers) were all agreed was that man’s will remains free; we are responsible for our acts… Although we have only cited these two (Ambrose and Ambrosiaster), there is little doubt that their views were representative (of the Western Fathers)… ‘It is for God to call’, remarks Jerome, ‘and for us to believe’. The part of grace, it would seem, is to perfect that which the will has freely determined; yet our will is only ours by God’s mercy.’

[23] John Calvin, Institutes, book 2, chapter 2, section 4 writes,

‘Moreover although the Greek Fathers, above others, and especially Chrysostom, have exceeded due bounds in extolling the powers of the human will, yet all ancient theologians, with the exception of Augustine, are so confused, vacillating, and contradictory on this subject, that no certainty can be obtained from their writings.’

[24] Kaia Stern, Voices from American Prisons: Hope, Education, and Healing (New York: Routledge, 2015), p.39

[25] Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011); J. Kameron Carter, Race: A Theological Account (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). ‘Europe’ was perceived as ‘Christian,’ and therefore ‘whiteness’ was so perceived as well. Of course, the lure of wealth helped a great many Europeans see non-Europeans as sub-human tools, treacherous but useful in the fields and the mines, not beloved by God. For example, when the Spanish Dominican friar Bartolome de las Casas defended the Taino people on the island of Hispaniola before the court of Spain, he first had to argue that they were actually human. Sadly, even he initially advocated the use of African slaves instead, though he repented of that view. Even when their full humanity was theoretically acknowledged insofar as evangelizing them was concerned, the myth of criminality rose to take its place to maintain their Augustinian ‘otherness.’ Bartolome de las Casas, A Short Account of the Devastation of the Indies (1561)

[26] Westminster Confession of Faith, chapter 33, paragraph 2

[27] John Piper, How Does it Glorify God to Predestine People to Hell?, March 21, 2013; http://www.desiringgod.org/resource-library/ask-pastor-john/how-does-it-glorify-god-to-predestine-people-to-hell

[28] John Piper, How Does it Glorify God to Predestine People to Hell?, March 21, 2013; http://www.desiringgod.org/resource-library/ask-pastor-john/how-does-it-glorify-god-to-predestine-people-to-hell

[29] Jamelle Bouie, ‘Christian Soldiers,’ Slate, February 10, 2015

[30] Augustine of Hippo, Sermon 185 says, ‘Never would you have been freed from sinful flesh, had he not taken on himself the likeness of sinful flesh’; On the Trinity, book 13, chapter 16 says, ‘For by it [his death] nothing is lessened or changed from His divinity, and so great a benefit is conferred upon men from the human nature which He took upon Himself’; Enchiridion, paragraph 41 says, ‘He there [was made] sin, as we [were made] justice; not our justice, but that of God; not in ourselves, but in him; just as he [was made] sin, not his own sin, but our sin’; Against Faustus the Manichean, book 14, paragraphs 3 – 6; On Christian Doctrine, book 1, chapter 14; On the Christian Struggle (see Orthumanitas blog, March 31, 2015, http://orthumanitas.blogspot.com/2015/03/the-human-remedy.html); Thomas Weinandy, In the Likeness of Sinful Flesh: An Essay on the Humanity of Christ (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1993), p.29; Stanley P. Rosenberg, ‘Interpreting Atonement in Augustine,’ edited by Charles E. Hill and Frank A. James III, The Glory of the Atonement (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004) notes that Augustine did not believe in penal substitution, which is refreshingly honest for a book dedicated to penal substitution

[31] Augustine of Hippo, Confessions 1.19

[32] Augustine, Concerning the Nature of Good, Against the Manicheans chapter 38,

‘For neither is eternal fire itself, which is to torture the impious, an evil nature, since it has its measure, its form and its order depraved by no iniquity; but it is an evil torture for the damned, to whose sins it is due. For neither is yonder light, because it tortures the blear-eyed, an evil nature.’

[33] Catholic Encyclopedia, ‘Hell’, ‘Characteristics of the pains of hell’ (3) states, ‘a punishment symbolically described as a fire’; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07207a.htm; Wikipedia, ‘Christian Views on Hell,’ ‘Orthodox conceptions of hell’ (last accessed February 10, 2016); https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_views_on_hell

[34] See my paper, Hell as the Love of God: http://newhumanityinstitute.org/pdfs/article-hell-as-the-love-of-god.pdf

[35] Ambrose of Milan, On the Holy Spirit, book 1, chapter 14, paragraphs 164 – 165, 169 – 170; Jonathan Edwards, Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, ‘By the meer pleasure of God,’ section 10

[36] Timothy J. Gorringe, God’s Just Vengeance: Crime, Vengeance, and the Rhetoric of Salvation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p.140