Post 7: A Neuroscientific Reason for Why Retributive Justice is from the Fall, and Penal Substitution is Immature

Can Offenders Grow?

Neuroscientist Daniel Reisel studied the brains of psychopathic murderers. He gauged their responses to pictures of people’s emotional expressions. Using MRI’s to image their brains, Reisel found a deficit in the amygdala, a region of the brain we believe to be the ‘location’ of empathy. But Reisel and other neuroscientists also have hope. They also discovered that new brain cells can develop, even in adult brains. While isolation and stress can suppress the growth of new brain cells, human interaction and relationship stimulate the brain to develop new cells. Dr. Reisel says, in a TED talk called The Neuroscience of Restorative Justice, that the brains of offenders are further damaged especially by solitary confinement, and imprisonment when not accompanied by other humanizing, relational activities:

‘It is ironic that our current solution for people with stressed amygdalas is to place them in an environment that actually inhibits any chance of further growth. Of course, imprisonment is a necessary part of the criminal justice system and protecting society… [But] because our brains are capable of change, we need to take responsibility for our actions, and they need to take responsibility for their rehabilitation.’[1]

To reduce reoffending rates, and reimprisonment, Dr. Reisel recommends restorative justice practices:

‘One way such rehabilitation might work is through restorative justice programs. Here, victims, if they choose to participate, and perpetrators, meet face to face in safe, structured encounters. The perpetrators is encouraged to take responsibility for their actions. The victim plays an active role in the process. In such a setting, the perpetrator can see, perhaps for the first time, the victim as a real person with thoughts and feelings and a genuine emotional response. This stimulates the amygdala, and may be a more effective rehabilitative practice than simple incarceration. Such programs won’t work for everyone. But for many, it could be a way to break the frozen sea within.’[2]

I have already blogged about examples of restorative justice here. It is a good option. However, we face a challenge in embracing this option: our thirst for retribution. Reisel says:

‘Finally, I believe we need to change our own amygdalas. Because this issue goes to the heart not just of who [a murderer] is, but who we are. We need to change our view of Joe as someone wholly irredeemable. Because if we see [a murderer] as wholly irredeemable, how will see himself as any different?’[3]

Another neuroscientist, Pascal Boyer, also argues that the human brain seems to respond to ‘karmic justice’ as a principle. That is, men and women seem wired to believe in retributive justice on the cosmic level. Journalist Casey Luskin writes a fairly readable summary of Dr. Boyer’s argument:

‘Humans are pattern-seekers from birth, with a belief in karma, or cosmic justice, as our default setting.’[4]

Karmic retributive justice! This brain wiring suggests why the most deeply philosophical forms of ancient Hindu and ancient Greek cosmology alike agreed about cycles of karma, reincarnation, and the principle of retribution. That view of the world just makes more sense to us intuitively. It also concurs with the more natural observations of how the world works: in endless cycles and circles.

Another journalist connects this neurological wiring for karmic justice to our taste for literature, both mythic and modern. When people ‘get what they deserve’ in a story, it touches a certain part of our brains:

‘Indeed, it appears that stories exist to establish that there exists a mechanism or a person—cosmic destiny, karma, God, fate, Mother Nature—to make sure the right thing happens to the right person. Without this overarching moral mechanism, narratives become records of unrelated arbitrary events, and lose much of their entertainment value. In contrast, the stories which become universally popular appear to be carefully composed records of cosmic justice at work.

‘In manuals for writers (see “Screenplay” by Syd Field, for example) this process is often defined in some detail. Would-be screenwriters are taught that during the build-up of the story, the villain can sin (take unfair advantages) to his or her heart’s content without punishment, but the heroic protagonist must be karmically punished for even the slightest deviation from the path of moral rectitude. The hero does eventually win the fight, not by being bigger or stronger, but because of the choices he makes.

‘This process is so well-established in narrative creation that the literati have even created a specific category for the minority of tales which fail to follow this pattern. They are known as “bleak” narratives.’[5]

Let’s pause and consider what (at least some) neuroscience is telling us about ourselves: Restorative justice practices work better than retributive justice practices in reducing criminal behavior. We see that empirically. We also understand why: Our amygdalas produce more healthy brain cells when we are in constructive relationships with others. And yet the ‘default setting’ (said tentatively) of our brain is karmic retributive justice! At least with some wrong-doers, and people we feel unable to trust, we simply desire to punish them. We isolate them in massive prisons. We put them out of our sight. We stop caring about them. Often, when they get out of prison, we continue to penalize them by denying them voting rights, food stamps, public housing eligibility, many types of employment, and relief from indebtedness. So ‘we need to change our own amygdalas,’ as Dr. Daniel Reisel says.

Does that strike you as odd? And do you see the theological implications?

In other words, we now know that the ‘criminalized other’ needs something from us. But we also resist giving it. Yet, unfortunately, when we live out of this ‘karmic retributive justice’ mode, we further damage people who are already damaged. Our own amygdalas need to be challenged and stretched. For the sake of others, and ourselves.

To be precise, we need to outgrow our desire for retributive justice. We need to grow into restorative justice. These two assertions from neuroscientists – (1) that our default brain setting is karmic retributive justice, and yet (2) that restorative justice works – attest to the biblical fall into corruption (including a corrupted mind!) and our need for redemption. We now know what is best for us, and yet something in our very brains resists doing the good we know. Even sinners reciprocate good for good and evil for evil. Only Jesus fully desires good, fully wills good, and fully does good. He actively loves his enemies and seeks their highest good: their restoration to himself so we can be the people God always intended us to be. And he calls us to share in his love and his perspective so that we might become people of grace and truth, kind reconciliation and firmly rooted integrity.

Now, to the extent that neuroscience is a field that is still young and developing, there may be more light shed on this in the future which may cause us to refine our statements. These studies try to sample people from multiple cultures and religions, but there may be social conditioning at work on the brain. For example, I have not seen a neuroscientist attempt to explain why human beings, broadly speaking, prior to the second millenium BC seem to have not linked religion with morality (which is not to say that no such attempts exist, only that I do not know of any). And we cannot study the brains of people who lived four thousand years ago, so it would not be a neuroscientific study per se, only a neuroscientist speculating on human history, which is vastly different. But to the extent that these are tentative, but so far reasonable, resting points in neuroscience, I want to draw them into the field of discussion of Christian theology and ethics.

This is one more reason – a neuroscience-based one – why I believe penal substitution is mistaken. Penal substitution perceives God’s justice to be retributive. Medical substitution, by comparison, perceives God’s justice to be restorative.

For those of you who would appreciate a reminder of what these theological positions are, here’s a quick recap. Penal substitution is a theory in Protestant evangelical theology. In this theory, we are ‘saved’ by Jesus from God’s retributive wrath. Jesus substitutes himself in for us as the one who bore our legal punishment from God. In the background, what is happening in the character of God that makes this necessary? In this theory, God experiences an inner conflict over us because of our sinful actions. On the one hand, He takes offense infinitely and therefore desires to retributively punish us infinitely for our sinful actions. God will be a kind of relentless tormentor in hell, which will be His prison for all those He will actually punish. Simultaneously, in this theory, God feels affection and mercy towards us and therefore a desire to pardon us – some of us, that is.[6] So God directs some of His retributive punishment onto Jesus at the cross, instead of on all of us in hell. And in that sense, God dispenses His forgiveness and love on some people, but only after first dispensing infinite retribution on Jesus. While God shows mercy to some, He pours infinite retributive justice upon Jesus and those in hell. Thus, God’s retributive justice is the larger category, larger than His mercy. Penal substitution makes retributive justice the default setting of God’s character.

Medical substitution, by contrast, is my nickname for the view held by the earliest Christians, the entire Eastern Orthodox communion, and those Roman Catholics and Protestants who are interested in exploring historic, early Christianity. In this theory, we are saved by Jesus from our own sinfulness, not from God. Jesus substitutes himself in for us in our responsibility to heal our own human nature in partnership with God. The role of Jesus is to share in our fallen human nature, so we could share in his healed human nature. That is, Jesus struggled to resist every temptation and return his human nature cleansed and purified to the Father. Jesus’ death was not him absorbing divine retributive punishment for us. Rather, it was his final victory over the corruption of sin within himself, as he killed it, so he could rise into new, resurrection life without it. Only then could Jesus share himself with us by his Spirit, to empower us to live accordingly. So, God does for us – in Christ – what we could not do for ourselves: perfect our own human nature with God. In the background, what is happening in the character of God that makes this necessary? God does not and cannot experience an inner conflict between attributes, because He is what theologians call ‘simple.’ That is, He does not have ‘parts.’ So how do God’s wrath and God’s love relate to each other? His wrath is directed at the corruption of sin in us, but not our personhood, much like the wrath of a surgeon is directed at the cancer in our bodies, but not at us. In fact, God’s wrath is an activity or expression of His love, because God desires to cut something away from us (hence the Jewish idiom of ‘circumcision of the heart’ in Dt.30:6). Medical substitution makes restorative justice the default setting of God’s character.

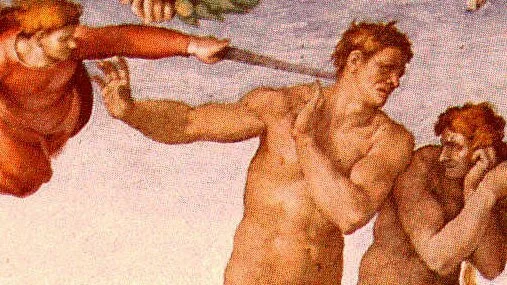

Take the fall of humanity in Genesis 3 as a case study in how these two major camps tend to interpret God. Many Protestant evangelicals, influenced by the penal substitution view, assert that God retaliated against Adam and Eve by inflicting death upon them. But was God’s imposition of death a retributive punishment? Was God really saying, ‘You caused me pain, so I’ll cause you pain’? No. The earliest Christians didn’t see it that way because they were firmly rooted in a medical and restorative view of God’s character. Irenaeus, bishop of Lyons (130 – 202 AD), interpreted death as an act of mercy. Death was better than Adam and Eve eating from the tree of life in a corrupted state and making their own human evil immortal:

‘Wherefore also He drove him out of Paradise, and removed him far from the tree of life, not because He envied him the tree of life, as some venture to assert, but because He pitied him, [and did not desire] that he should continue a sinner for ever, nor that the sin which surrounded him should be immortal, and evil interminable and irremediable. But He set a bound to his [state of] sin, by interposing death, and thus causing sin to cease, putting an end to it by the dissolution of the flesh, which should take place in the earth, so that man, ceasing at length to live to sin, and dying to it, might begin to live to God.’[7]

In other words, according to Irenaeus, God was not acting retributively, but restoratively. Nor was Irenaeus alone in this opinion. Methodius, bishop of Olympus (died circa 311 AD), said the same:

‘In order, then, that man might not be an undying or ever-living evil, as would have been the case if sin were dominant within him, as it had sprung up in an immortal body, and was provided with immortal sustenance, God for this cause pronounced him mortal, and clothed him with mortality… For while the body still lives, before it has passed through death, sin must also live with it, as it has its roots concealed within us even though it be externally checked by the wounds inflicted by corrections and warnings… For the present we restrain its sprouts, such as evil imaginations, test any root of bitterness springing up trouble us, not suffering its leaves to unclose and open into shoots; while the Word, like an axe, cuts at its roots which grow below. But hereafter the very thought of evil will disappear.’[8]

Gregory of Nazianzus (329 – 390 AD), a bishop in modern day Turkey, also repeated the idea that God was not retributively punishing Adam and Eve, but already looking to restore them:

‘Yet here too he makes a gain, namely death and the cutting off of sin, in order that evil may not be immortal. Thus, his punishment is changed into a mercy, for it is in mercy, I am persuaded, that God inflicts punishment.’[9]

What’s so significant about these three early theologians? Irenaeus was led to faith by Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, who was himself mentored by the apostle John. This occurred at a time when Asia Minor, including Smyrna, was the intellectual and missionary center of the Christian faith, not least because Paul, Peter, and John all invested enormous time and effort there. Irenaeus was the first to explicitly quote from all four Gospels, and was the first biblical theologian – outside of the apostles – to write extensively. So the likelihood is high that Irenaeus acquired his understanding of Genesis fully intact from the apostle John, and behind John, Jesus himself. Methodius, bishop of Olympus, was a contemporary of the great Origen of Alexandria. Methodius was one of the only church leaders who raised concerns about worrying trends in Origen’s thought. And Gregory, bishop of Nazianzus, was one of the most significant Christians ever. The Orthodox church calls him ‘the Theologian’ in appreciation for his thoughtful and precise work in the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381 AD and the intense fourth century debates with heretics. The Orthodox bestow that title only on two others: the apostle John ‘the Theologian’ and Simeon ‘the New Theologian.’ For these great Christian leaders to corroborate one another explicitly on this issue is weighty. They attest to the unanimous church opinion on this issue.

How were they reading Genesis 3? Biblically, they read Adam and Eve as forcing God to curtain off the garden and withdraw His presence to some degree. That is a very reasonable interpretation. The fall was more like Adam and Eve trying to lock God out of the house, and trying to go about life on their own, as rebellious young children in a great house. God had made Adam and Eve to bring forth life – both human life and garden life. God would mercifully ensure that they would be able to carry out their original calling, albeit in a limited form. After all, God’s promise of a messianic ‘seed of the woman’ who would redeem human nature and defeat the serpent (Gen.3:14 – 15) depended on their ability to have children. But the sorrows in childbirth and gardening, along with physical death, took hold of humanity because Adam and Eve pushed God, the life-giver, aside. As Adam and Eve tried to bring forth life, they would have a harder time. So the early Christians read the sorrows of childbirth and gardening in Genesis 3:16 – 19 as already anticipating the closing off of the garden in Genesis 3:22 – 24. The sorrows were not a retributive punishment. It was not God playing tit for tat. Rather, the sorrows in life-bearing were God as the life-source being forced by His love to withdraw from His life-bearers. He would not have Adam and Eve suffer a fate worse than death. Anything was better than immortalized sinfulness. Death was a severe mercy, but a mercy nonetheless. It played a positive role in God’s larger plan of restoration.

When I share this interpretation and the quotes above, I am often met with wide-eyed wonder. Most Protestant evangelicals have never heard Genesis 3 interpreted this way. They ask:

But didn’t God punish Israel when Israel sinned?

Didn’t God instruct Israel to take an eye for an eye, as a reflection of His own character?

Isn’t New Testament mercy hanging on the backdrop of an Old Testament which is about retributive justice?

And isn’t the fire of hell a retributive punishment for our sin?’

Here are quick answers to those questions.

No, God did not punish Israel for every sin (Ps.103:10), especially not in the same way we typically punish criminals in Western jurisprudence.[10]

No, God did not intend for ‘an eye for an eye’ to be an automatic principle but only an outer limit of proportionality to limit the victim in requesting compensation of labor or payment for injury (Ex.21:22, 30 which appears early because it is meant to carry through in our reading of the entire Jewish law). So the ethics of the Jewish law are fundamentally restorative, not retributive. That matches God’s character.

No, the Old Testament as a whole is about restorative justice, not retributive justice, as shown by (1) God’s interactions with people in Genesis, prior to the Sinai covenant; and (2) God’s promises to restore Israel to be His truly human beings living in a truly beautiful garden land.

And no, ‘fire,’ in the biblical books where it appears as a literary theme, is first and foremost an emblem of the purifying love of God; so ‘fire’ in hell represents God’s call to surrender to His purification those who eternally resist because of the addictive quality of sin.[11] Even in hell, God cannot help but call the rebellious to restoration, despite their own eternal resistance.

Bringing these neuroscience studies together with medical substitutionary atonement helps us do evangelism. A friend of mine once challenged me by posting on my Facebook wall a video by a Dr. Andy Thomson. Thomson is a neuroscientist and atheist. He gave a talk called ‘Why We Believe in Gods’ at the American Atheist convention in 2009 in Atlanta, GA.[12] In it, he says that religions ‘hijack’ the human brain. The human brain looks for love, and more importantly, for patterns of justice. I replied with this:

‘A more recent, and more precise, piece comes from July 2014 and is referenced by Casey Luskin on August 1, 2014 in his readable article: ‘Evolutionary Studies Suggest that Atheists, Whatever They Say to the Contrary, Really Do Believe in God,’ Evolution News and Views, August 1, 2014; http://www.evolutionnews.org/2014/08/evolutionary_st088461.html. Note the study citing “karmic justice” (that is, cosmic retributive justice) as the “default setting” for the “religious part” of our brains.

‘This poses a problem for you. I underscore that this finding comes from the current understanding of cognitive neuroscience. Since that is the case, it helps to explain to me why, when John Calvin developed the idea of penal substitution, that theory played on the “karmic justice” section of the human brain and then served to supplant the theological structure of genuine Trinitarian thought. Christian Trinitarian theology for the first 1500 years was not aligned with the “default setting” of our brains. Instead, Christian leaders basically called for their listeners and readers to participate with God in the rewiring of our brains. Let that soak in. The earliest atonement theory was medical and not penal. The implications for relationships and socio-political ethics was for restorative justice and not retributive justice. And as we have discussed before, the biblical motif of fire was interpreted as rehabilitative and purifying, not retributive and punishing.

‘So: Christian theology and teaching of this type (firmly held by the Eastern Orthodox, along with Catholics and Protestants like me who are calling for a return to the Nicene period) has to consistently overcome something deeply wired in our brains. It does not take advantage of the brain, or “hijack” the brain, as Dr. Andy Thomson states… Entertaining as videos like this are, nothing conclusive can be drawn from it, except that some practitioners of neuroscience overstate themselves.’

(The language of the brain having a ‘religious part’ or a ‘default setting’ for it comes from these journalists, and may very well be subject to question.) The traditions that come from Luther and Calvin served to supplant the theological structure of genuine Christian thought. My best guess is that penal substitution also impacted human brain development in the wrong direction. I substantiate my point by noting again[13] that American evangelicals have a very refined taste for retributive justice: A century ago, white evangelicals supported the lynching of African Americans as a retributive punishment for transgressing the ‘white social order.’ Evangelicals defended the Vietnam War when the rest of the country did not. The Southern Baptist Convention, in America the largest Protestant denomination and the second largest denomination next to Roman Catholics, officially supported the Iraq War. Today, evangelicals favor capital punishment more than the overall population. Evangelicals are more likely than the general population to justify torture of terrorists or even suspected terrorists. The Pew Research Trust reports that the percentage of people agreeing with the use of torture increases with the frequency of attending a religious service. I suspect, too, that evangelicals – especially white evangelicals – find it difficult to sympathize with the Black Lives Matter movement against police brutality, because they find it hard to believe that police retribution is at times partial or prejudiced. I suspect that their affection for the principle of meritocratic-retributive justice is the reason why American evangelicals tend to fault the poor for ‘failing at capitalism,’ oppose social welfare efforts, favor longer prison sentences for felons, and not guard against the excessive spanking of children.

So how do I interpret people who support penal substitution? With deep concern for brothers and sisters in Christ who are spiritually and neurologically immature. Some people might be actively committed to penal substitution, aggressively promoting it. Or some might be passively committed, wanting to ‘maintain a space’ for it while also deploying other explanations for why Jesus is important. Either way, despite their good intentions, if people are committed to penal substitution, their commitment is partially energized by a fallen brain. Penal substitution finds fertile soil in a facet of our brains that is immature and needs to be outgrown.

In his masterpiece The Lord of the Rings, Roman Catholic author J.R.R. Tolkien cautions us to uphold a Christian restorative justice. When the Company realized that the fallen hobbit-like creature Gollum was following them, Frodo expressed to Gandalf his revulsion towards Gollum. He said that it was a pity that Bilbo did not kill him. Gandalf, however, disagreed:

‘Pity? It was Pity that stayed his hand. Pity, and Mercy: not to strike without need. And he has been well rewarded, Frodo. Be sure that he took so little hurt from the evil, and escaped in the end, because he began his ownership of the Ring so. With Pity.’

‘I am sorry,’ said Frodo. ‘But I am frightened; and I do not feel any pity for Gollum.’

‘You have not seen him,’ Gandalf broke in.

‘No, and I don’t want to,’ said Frodo. I can’t understand you. Do you mean to say that you, and the Elves, have let him live on after all those horrible deeds? Now at any rate he is as bad as an Orc, and just an enemy. He deserves death.’

‘Deserves it! I daresay he does. Many that live deserve death. And some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them? Then do not be too eager to deal out death in judgement. For even the very wise cannot see all ends. I have not much hope that Gollum can be cured before he dies, but there is a chance of it. And he is bound up with the fate of the Ring. My heart tells me that he has some part to play yet, for good or ill, before the end; and when that comes, the pity of Bilbo may rule the fate of many – yours not least. In any case we did not kill him: he is very old and very wretched. The Wood-elves have him in prison, but they treat him with such kindness as they can find in their wise hearts.’[14]

Of course, Gandalf was quite correct about Gollum’s future, because Gollum became the one to destroy the Ring and himself. But Gandalf never made the fallen Gollum into a tool, a mere means to an end. Instead, Gandalf hoped for even Gollum’s restoration, a restoration that only Gollum could willingly choose because of the addictive properties of evil. When Gandalf considered whether the Ring could just be forcibly removed from Gollum, he said:

‘‘But that, of course, would only make the evil part of him angrier in the end – unless it could be conquered. Unless it could be cured.’ Gandalf sighed.’[15]

Gandalf’s is the divine perspective. Gandalf saw through the fault to the need. The creature Gollum committed grievous betrayals and crimes, but none so terrible as the injury he did to himself. He cultivated this cruel addiction in himself, which disfigured him and warped his mind so that all good things – from sunlight and starlight to friendship and love – brought him pain. Gandalf hoped that Gollum would choose differently, turn towards the life he was meant to have, and become the person he was meant to be.

If Tolkien’s great story evokes nobler impulses in us, and beckons us into our own sacred journeys, perhaps it is because something in us recognizes that retributive justice – even on the divine level, purportedly – is too simplistic and wrongheaded. We are, in fact, called to hope for the restoration of all persons and relations, and thus to grow. For we are made in the image of a God of restorative, not retributive, justice. This God conquers that evil part. This God cures. In love, He calls for our partnership.

In other words, with the Spirit of Christ, we need to change our own amygdalas.

[1] Daniel Reisel, ‘The Neuroscience of Restorative Justice,’ TED Talk, February 2013; http://www.ted.com/talks/daniel_reisel_the_neuroscience_of_restorative_justice#t-568852

[2] ibid

[3] ibid

[4] Casey Luskin, ‘Evolutionary Studies Suggest that Atheists, Whatever They Say to the Contrary, Really Do Believe in God,’ Evolution News and Views, August 1, 2014; http://www.evolutionnews.org/2014/08/evolutionary_st088461.html

[5] Nury Vittachi, ‘Scientists Discover That Atheists Might Not Exist, and That’s Not a Joke,’ Science 2.0, July 6, 2014; http://www.science20.com/writer_on_the_edge/blog/scientists_discover_that_atheists_might_not_exist_and_thats_not_a_joke-139982

[6] See Interpreting Jesus and Atonement – Practical Issue #1: Does God Love Your Non-Christian Friend? (https://newhumanityinstitute.wordpress.com/2015/08/17/interpreting-jesus-and-atonement-practical-issue-1-does-god-love-your-non-christian-friend/)

[7] Irenaeus of Lyons, Against Heresies 3.23.6

[8] Methodius of Olympus, From the Discourse on the Resurrection, Part 1.4 – 5

[9] Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration 45

[10] As I wrote in my last blog post, Atonement in Scripture: Why Trump and Cruz Are the Direct, Logical Result of American Evangelical Theology (https://newhumanityinstitute.wordpress.com/2016/03/05/atonement-in-scripture-why-trump-and-cruz-are-the-direct-logical-result-of-american-evangelical-theology/): True, there are incidents where God punished and disciplined Israel as a whole. Activity of that nature, though, took the form of other nations enslaving the Israelites and taking Israel captive because they either stopped relying on God, and/or they made alliances with these foreign powers. King Hezekiah sought an alliance with Babylon (Isaiah 39); prior to that, King Ahaz seemed to want an alliance with either Assyria or the combination of Aram and the Northern Kingdom of Israel (Isaiah 7). So Assyria invaded the Northern Kingdom of Israel, and later, Babylon invaded the Southern Kingdom of Judah. In other words, this was the natural course of human choices. The Jewish people perceived themselves as an ordinary nation. They either relied on ordinary human ‘strength’ or made diplomatic ties inviting foreign influence. Those foreign influences took over. Even though the language of God’s ‘retribution’ is sometimes used in the context of Old Testament Israel, the substance was not a tit-for-tat response to Israel’s sin, which is what Western jurisprudence makes of the term ‘retribution.’

These were regime-changes meant to reenact Israel’s captivity to Egypt. Captivity expressed to Israel that they were in spiritual and historical regression. What they were experiencing in a geo-political sense was the concrete manifestation (revelation) of a spiritual posture of abandoning God as the true king of Israel. The experience was intended as pedagogy. Paul saw this same dynamic in Romans 1:21 – 32 when he said, ‘God gave them over,’ as did Jeremiah before him:

19 ‘Your own wickedness will correct you,

And your apostasies will reprove you;

Know therefore and see that it is evil and bitter

For you to forsake the LORD your God,

And the dread of Me is not in you,’ declares the Lord GOD of hosts.

20 ‘For long ago I broke your yoke

And tore off your bonds;

But you said, ‘I will not serve!’…

28 ‘But where are your gods

Which you made for yourself?

Let them arise, if they can save you

In the time of your trouble… (Jeremiah 2:19 – 20, 28)

Most people would call this ‘poetic justice,’ but not ‘retributive justice’ in the strict and formal sense we in the West have come to expect. Moreover, even those events were excessively violent due to human factors beyond God’s intention:

14 So the angel who was speaking with me said to me,

‘Proclaim, saying, ‘Thus says the LORD of hosts,

‘I am exceedingly jealous for Jerusalem and Zion.

15 But I am very angry with the nations who are at ease;

for while I was only a little angry, they furthered the disaster.’ (Zechariah 1:14 – 15)

1 ‘Comfort, O comfort My people,’ says your God.

2 ‘Speak kindly to Jerusalem; and call out to her,

That her warfare has ended, that her iniquity has been removed,

That she has received of the LORD’S hand double for all her sins.’ (Isaiah 40:1 – 2)

So Babylon did more than God intended. Zechariah’s and Isaiah’s evaluation of the Babylonian invasion raises important questions of theodicy and the mode of God’s sovereignty, which I’ve discussed elsewhere (Suffering and the Sovereignty of God’s Word, http://newhumanityinstitute.org/pdfs/article-suffering-&-the-sovereignty-of-god’s-word.pdf). But for my purpose here, this too casts sufficient doubt on the notion that Western jurisprudence, which is meant to maintain the philosophical and social legitimacy of the regime doing the punishing, can be calibrated to the regime-changing events Israel experienced. God’s relationship with Israel cannot be reduced to expressions of Western jurisprudence.

[11] For example in Luke – Acts, the Holy Spirit is announced as coming as a purifying fire (Lk.3:16), and then comes at Pentecost with tongues of fire (Acts 2:3). See my earlier blog post, Interpreting Jesus and Atonement – Practical Issue #4: What About Hell?, https://newhumanityinstitute.wordpress.com/2015/08/20/interpreting-jesus-and-atonement-practical-issue-4-what-about-hell/.

See also The Theme of Fire in the Pentateuch, The Theme of Fire and Purification in Isaiah, The Theme of Fire in Matthew: What is Divine Fire?, The Theme of Fire in Revelation: What is Divine Fire? found here: http://www.anastasiscenter.org/gods-goodness-fire.

[12] Dr. Andy Thomson, ‘Why We Believe in Gods’ American Atheist Convention 2009: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1iMmvu9eMrg

[13] For citations, see footnotes 27 – 30 in Atonement in Scripture: Why Trump and Cruz Are the Direct, Logical Result of American Evangelical Theology (https://newhumanityinstitute.wordpress.com/2016/03/05/atonement-in-scripture-why-trump-and-cruz-are-the-direct-logical-result-of-american-evangelical-theology/)

[14] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, chapter 2

[15] Ibid, book 2, chapter 2