Athanasius as Evangelist, Part 8: More on the Nicene Creed and Penal Substitution As Incompatible

John Calvin and Athanasius of Alexandria

John Calvin’s distaste for Athanasius has recently been noted by Thomas G. Weinandy, one of the most respected scholars in the Catholic Church, former executive director for the Secretariat of Doctrine at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, and Daniel A. Keating, professor of theology at Sacred Heart Major Seminary. They say:

‘The one notable exception to this warm reception of Athanasius [among early Protestants] is John Calvin. He makes no positive use of Athanasius and when pressed about whether he subscribed to the three creeds [Apostles’, Nicene, and Athanasian], replied that he ‘had pledged his faith to the one God, not to Athanasius…’ For the Reformers, the translation of Athanasius’ corpus into Latin was not a landmark event as was the publication of the Greek New Testament. They were not so much captivated by a rediscovery of the fathers for their own sake as they were interested in gathering from the patristic texts testimony to the truths of the faith and the reforms of the church they sought to enact.’[1]

This is not surprising. Calvin argued that Jesus descended into hell after his death and was separated from his Father:

‘If Christ had died only a bodily death, it would have been ineffectual. No — it was expedient at the same time for him to undergo the severity of God’s vengeance, to appease his wrath and satisfy his just judgment. For this reason, he must also grapple hand to hand with the armies of hell and the dread of everlasting death… No wonder, then, if he is said to have descended into hell, for he suffered the death that, God in his wrath had inflicted upon the wicked!’[2]

However, Athanasius explicitly rejected all of the premises from which Calvin worked. For Athanasius, God did not ‘appease his wrath and satisfy’ his retributive justice over human beings breaking His commands.

‘Had it been a case of a trespass only, and not of a subsequent corruption, repentance would have been well enough; but when once transgression had begun men came under the power of the corruption proper to their nature and were bereft of the grace which belonged to them as creatures in the Image of God. No, repentance could not meet the case. What – or rather Who – was it that was needed for such grace and such recall as we required? Who, save the Word of God Himself, Who also in the beginning had made all things out of nothing?’[3]

Athanasius did not locate the ‘divine dilemma’ in God’s supposed need to punish. Later Calvinist theologian R.C. Sproul asserts, ‘Sin against an infinite being demands an infinite punishment in hell.’[4] Athanasius would have none of that. Rather, the earlier theologian located the ‘divine dilemma’ in God’s need to heal human nature once it became corrupted, because He loved us.

‘So, as the rational creatures were wasting and such works in course of ruin, what was God in His goodness to do? Suffer corruption to prevail against them and death to hold them fast? And where were the profit of their having been made, to begin with? For better were they not made, than once made, left to neglect and ruin. For neglect reveals weakness, and not goodness on God’s part— if, that is, He allows His own work to be ruined when once He had made it— more so than if He had never made man at all. For if He had not made them, none could impute weakness; but once He had made them, and created them out of nothing, it were most monstrous for the work to be ruined, and that before the eyes of the Maker. It was, then, out of the question to leave men to the current of corruption; because this would be unseemly, and unworthy of God’s goodness.’[5]

And, as I explore in this blog post, Athanasius rejected any suggestion that a separation opened up between the Father and the Son in any sense. He rejected any notion that at the cross, the Father suddenly acted upon the Son rather than continued to act in and through the Son by the Spirit. He rejected the idea that the Son had a separate consciousness from the Father such that Jesus lost his awareness of the Father. In fact, Athanasius provides an interpretation of Jesus’ cry of forsakenness from the cross (‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’) that directly opposes the interpretations offered by penal substitution advocates like Luther and Calvin. Although my own exegetical explanation of Jesus’ cry differs slightly from Athanasius’,[6] I wholeheartedly agree with him about this:

‘Neither can the Lord be forsaken by the Father, who is ever in the Father, both before He spoke, and when He uttered this cry.’[7]

Penal substitution did not exist in the mind of Athanasius, and could not have existed. The nature of the Father-Son relationship prevented it.

Defining Salvation Carefully

Why is that? Salvation was defined as God’s personal union with human nature, recovering humanity from sin, death, and the demonic. This conviction about salvation drove orthodox reflection about christology, and therefore the Trinity. Looking at the theological structure from the standpoint of its ‘atonement theology,’ we can see that the definition operating in the mind of Athanasius is that the eternal Son of God, who is one substance with the Father, shared our fallen human nature in order that we might share his healed human nature, by the Spirit. Jesus paid the price of carrying human nature on his shoulders and having to struggle through its fallen, weakened state. He shared in the punishment that we bear after the fall – corruption and death – in order to make a way through it for us. This is exactly ‘medical substitutionary atonement,’ or ‘ontological substitutionary atonement,’ although it has certainly gone by other names.

Not only does Athanasius not speak of atonement in the legal-penal paradigm of retributive justice required by penal substitution, but he instead employs a medical-ontological paradigm to support the Father-Son relation he understood from Scripture.

In fact, the development of the church consensus around the Nicene doctrine of the Trinity in 325 AD and the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381 AD rest on the understanding of atonement and salvation that can be nicknamed ‘medical substitutionary atonement.’ This nomenclature invites direct comparison with ‘penal substitution.’ The bishops in the first two Ecumenical Councils were guided by the larger theological thought structure which is described by the phrase deployed succinctly by Gregory of Nazianzus, ‘That which is not assumed is not healed.’ If true divinity did not personally unite with true humanity in the person of Jesus, then there is no salvation.

In this understanding, there is no separation between Father and Son. I will glance at two works of Athanasius here: Discourses Against the Arians 1 – 2 and Defense of the Nicene Definition.

Athanasius’ Contra Arianos 1 – 2 and De Decretis

When Athanasius embarked on his second exile from Alexandria, he went to Rome to seek the shelter and support of Julius, bishop of Rome. While there, perhaps encouraged by the anti-Arian Julius and also by the death of their archrival Eusebius, bishop of Nicomedia, in 341 or 342, Athanasius probably composed the first and second Discourses Against the Arians / Contra Arianos. These lengthy refutations of Arian prooftexts show Athanasius’ ability as a biblical expositor of these key texts. They also glitter with insights into Athanasius’ mind as a biblical theologian and pastoral bishop.

Athanasius explains the Nicene Council itself in his work Defense of the Nicene Definition, or De Decretis, written between 346 – 356 AD, shortly after Contra Arianos. He insists from Scripture and logic that dividing the Father, Son, and Spirit up into separate centers of consciousness smuggles in the inappropriate connotation that each person possesses his own corporeal body. Significantly, Athanasius says the word homoousion (‘same essence’ or ‘one in essence’) was used in the Nicene Creed to prevent that connotation:

‘For bodies which are like each other may be separated and become at distances from each other, as are human sons relatively to their parents (as it is written concerning Adam and Seth, who was begotten of him that he was like him after his own pattern [Genesis 5:3]); but since the generation of the Son from the Father is not according to the nature of men, and not only like [the essence], but also inseparable from the essence [ek tis ousia] of the Father, and He and the Father are one, as He has said Himself, and the Word is ever in the Father and the Father in the Word, as the radiance stands towards the light (for this the phrase itself indicates), therefore the Council, as understanding this, suitably wrote ‘one in essence [homoousios],’ that they might both defeat the perverseness of the heretics, and show that the Word was other than originated things.’[8]

Athanasius asks us to consider an earthly fire that springs up from the heat of the sun. Then, he says, that is still not an appropriate analogy for the Son-Father relation. The physical separation between the fire on earth and the fire of the sun disqualifies it. There is no separation, Athanasius insists, between Father and Son:

‘Again, the illustration of the Light and the Radiance has this meaning. For the Saints have not said that the Word was related to God as fire kindled from the heat of the sun, which is commonly put out again, for this is an external work and a creature of its author, but they all preach of Him as Radiance, thereby to signify His being from the essence, proper and indivisible, and His oneness with the Father.’[9]

Athanasius indicates that the Nicene Creed must be interpreted with disciplined attention to the Gospel of John because it is largely derived from there. John’s account speaks of the Father-Son relation in terms of a mutual indwelling at all times. ‘I am in the Father and the Father in Me,’ says Jesus (John 14:9 – 10; etc.). Therefore:

‘Let every corporeal reference be banished on this subject; and transcending every imagination of sense, let us, with pure understanding and with mind alone, apprehend the genuine relation of son to father, and the Word’s proper relation towards God, and the unvarying likeness of the radiance towards the light: for as the words ‘Offspring’ and ‘Son’ bear, and are meant to bear, no human sense, but one suitable to God, in like manner when we hear the phrase ‘one in essence [homoousion],’ let us not fall upon human senses, and imagine partitions and divisions of the Godhead, but as having our thoughts directed to things immaterial, let us preserve undivided the oneness of nature and the identity of light.’[10]

The Father as Fountain of Wisdom, and the Son Who is His Wisdom: 1.17 – 22

But that’s not all. Throughout Contra Arianos 1 – 2, Athanasius consistently explores Paul’s statement in 1 Corinthians 1:24 that ‘Christ is the wisdom and power of God,’ explicitly and implicitly.[11] Athanasius even ventures to say that the Father’s fullness is the Son (1.50), by quoting John 1:16. For Athanasius, that is an important point, because if we are given experience of God, and knowledge of God, in a true and proper way, then the Son must reveal the Father truly and properly. Hence, Athanasius says repeatedly that the Son is the Power and Wisdom of the Father.

The Son doesn’t share the Father’s attributes of Wisdom and Power. He is them, by personally being them.

In Contra Arianos 1.19, we also find Athanasius using his basic paradigm for explaining God: the image of a fountain overflowing itself.

‘If God [the Father] be, and be called, the Fountain of wisdom and life— as He says by Jeremiah, ‘They have forsaken Me the Fountain of living waters [Jeremiah 2:13]’ and again, ‘A glorious high throne from the beginning, is the place of our sanctuary; O Lord, the Hope of Israel, all that forsake You shall be ashamed, and they that depart from Me shall be written in the earth, because they have forsaken the Lord, the Fountain of living waters [Jeremiah 17:12 – 13]’… life and wisdom are not foreign to the Essence [ousia] of the Fountain, but are proper to It, nor were at any time without existence, but were always… Is it not then irreligious to say, ‘Once the Son was not?’ for it is all one with saying, ‘Once the Fountain was dry, destitute of Life and Wisdom.’ But a fountain it would then cease to be; for what begets not from itself, is not a fountain.’[12]

Athanasius is deploying the common patristic analogies about a sun with its radiance[13] and a fountain with its stream[14] to set the basic groundwork. The portrait of ‘something which overflows itself’ guides the early Christian imagery for the Father-Son relation, and eventually the Father-Son-Spirit relation.[15] The image of an overflowing fountain connects Jerusalem to Eden, which overflowed with water. The image of the sun and its overflowing radiance seems to inform Hebrews 1:1 – 3: ‘He [the Son] is the radiance of His [the Father’s] glory and the exact representation of His nature.’

This is not simply a clever metaphor. It is a reflection on Scripture. Athanasius quotes Jeremiah 17:12 – 13 which invokes, in Israel’s voice, ‘our sanctuary,’ which was modeled after Eden, a mountain (Ezk.28:13 – 14) and a fountain from which four rivers diverged (Gen.2:10 – 14, which informs Ezk.40 – 48). To describe Himself, God used the motif of this fountain, not just any fountain. Through Jeremiah’s voice, God invited His people to think of Him like this.

Athanasius is among many who accepted that invitation. He asserts that the Son is intrinsically proper to the Father as water is to a fountain. Just to name a fountain ‘a fountain’ is to indicate its water. Even so, just to name the Father ‘the Father’ is also to indicate his only-begotten Son. The Father is so intrinsically overflowing with life that he eternally begets the Son.

Whereas we speak of a human father and son sharing the same genetic human substance in spatially separate bodies, the relation between the divine Father and Son must be ‘tighter,’ and in any event conceived differently.

The Son is not simply another container ‘of the same stuff’ as the Father, whatever that divine ‘stuff’ is. The problem with this view, and indeed the reason why the Nicene Creed had its detractors, critics, and skeptics among Christian bishops following 325 AD, was that this would seem to lead to the inevitable conclusion that there were two Gods, one who is Father and another who is Son.[16] How was the church to confess on the one hand the divinity of the Son while still upholding one God, and, on the other hand, not collapse the Son into the Father, as in the Sabellian heresy?[17]

Athanasius’ answer is to draw on the fountain image. The Father’s Power is the Son. The Father’s Wisdom is the Son. Athanasius continues the passage quoted above by saying that if God promised to make us like fountains, He Himself must be one:

‘For God promises that those who do His will shall be as a fountain which the water fails not, saying by Isaiah the prophet, ‘And the Lord shall satisfy your soul in drought, and make your bones fat; and you shall be like a watered garden, and like a spring of water, whose waters fail not [Isaiah 58:11].’ And yet these, whereas God is called and is a Fountain of wisdom, dare to insult Him as barren and void of His proper Wisdom. But their doctrine is false; truth witnessing that God is the eternal Fountain of His proper Wisdom; and, if the Fountain be eternal, the Wisdom also must needs be eternal. For in It were all things made, as David says in the Psalm, ‘In Wisdom have You made them all [Psalm 104:24];’ and Solomon says, ‘The Lord by Wisdom has formed the earth, by understanding has He established the heavens [Proverbs 3:19].’ And this Wisdom is the Word, and by Him, as John says, ‘all things were made,’ and ‘without Him was made not one thing [John 1:3].’’[18]

He continues to argue that the Son must be the Father’s true essence if the Son is the Image and Radiance of the Father (1.20). Other attributes which belong to the Father must also belong to the Son: ‘eternal, immortal, powerful, light, King, Sovereign, God, Lord, Creator, and Maker’ (1.21). This much must be true if Jesus was truthful in saying that seeing him is seeing the Father (Jn.14:9).

The early church – Athanasius being an example – was persuaded that the Word of God, our creator, already providentially sustained us from creation. Like the earth partakes of the sun’s light, so we partake of him simply by the fact of our existence.[19] So the Son is the Father’s very Power, and very Wisdom.

Athanasius is Not Alone

Theologians of the early church other than Athanasius, in every major region of the Christian community, before and after him, asserted the same: (2nd century) Justin Martyr of Rome,[20] Theophilus of Antioch,[21] Irenaeus of Lyons,[22] Tertullian of Carthage,[23] Clement of Alexandria,[24] (3rd century) Origen of Alexandria,[25] Alexander of Alexandria,[26] Methodius of Olympus,[27] (4th century) the anti-Arian Council of Sardica in 343,[28] Cyril of Jerusalem,[29] Hilary of Poitiers,[30] Ambrose of Milan,[31] Basil of Caesarea,[32] Gregory of Nyssa,[33] Gregory of Nazianzus,[34] and John Chrysostom of Constantinople.[35] At least on occasion, Augustine of Hippo spoke this way as well.[36] This means the overwhelming consensus view of the church was that Christ is, and not merely shares in, the wisdom of God and the power of God. Neither ‘wisdom’ nor ‘power’ are abstractions or qualities that the persons of the Trinity share amongst themselves, or have in varying degrees. They believed that the Wisdom of God and Power of God were personal, that is, hypostatic: the very person of the Son. The dense, unanimous patristic consensus on this matter is significant historically, theologically, and exegetically.

How Did the Early Church Come to Confess This?

How did the Christian community come to speak this way? This consensus is significant as history because it was the orthodox view from so early, and for so long. The fact that the earliest Christian centers at Jerusalem, Antioch, Asia Minor, Alexandria, and Rome produced leaders who said this is a very weighty historical datum. The apostles invested very heavily in these areas. Adding Carthage in Roman North Africa, and Lyons in Roman Gaul to the list becomes quite impressive since tradition tells us that Christian faith was firmly established in these areas by the second century – Carthage may have been reached by a missionary team led by Crescens, ordained by Peter; Lyons and Southern Gaul were missionized by Greek-speakers from Asia Minor known and supported by Polycarp of Smyrna.

This was a standard, common, apostolic way of speaking about the Father-Son relation, not just the apostle Paul’s figure of speech in a single letter (1 Cor.1:24, 30). Of course, Christians did copy and circulate Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, and then the Gospel of John, relatively quickly. But I am not suggesting a narrow biblicism, or suggesting that Christianity be regarded as a movement of literature primarily. The Catholic and Orthodox conviction that Christian liturgy preceded the New Testament writings is really the only reasonable explanation here. For Athanasius is only one point of evidence bearing witness to this complete and total patristic consensus.

We must, of course, look to Jesus himself. Because ‘wisdom’ was such a prominent category in the Hebrew Scriptures, Christians could do little else but interpret it christocentrically. Jesus himself had referred to himself as ‘wisdom’ personified (Mt.11:19; Lk.7:35), and a teacher of ‘wisdom’ greater than Solomon (Mt.12:42; Lk.11:31). He even claimed to know the very mind of God, and speak for God, under the label of ‘the wisdom of God’ (Lk.11:49ff.). He certainly must have referred to himself as the truly ‘wise one,’ who internalized God’s commandments into his own humanity, which is what the ‘wise one’ of Proverbs was expected to do (Prov.1:23; 2:10; 3:3; 6:21; 7:3; cf.Dt.6:4 – 8; Jer.31:31 – 34). By saying, ‘Only the Son knows the Father,’ Jesus was placing himself into the role of Wisdom incarnate, since God’s Wisdom alone was thought to know God.[37]

The early Christians also interpreted ‘the power of God’ as Christ. Interestingly, they believed that all the epiphanies and encounters that people had with God in the Old Testament were encounters with the pre-incarnate Son. The second century apologist and teacher Justin Martyr is typical:

‘For I have proved that it was Jesus who appeared to and conversed with Moses, and Abraham, and all the other patriarchs without exception, ministering to the will of the Father; who also, I say, came to be born man by the Virgin Mary, and I lives for ever.’[38]

‘Our Christ conversed with him under the appearance of fire from a bush.’[39]

The early church derived this understanding from Jesus, who said he was the divine presence in the burning bush, who said, ‘I am’ to Moses (Jn.8:58). Also, Paul made the enigmatic remarks about Christ being ‘the rock’ which followed the Israelites in the wilderness (1 Cor.10:4). And Jude says in some manuscripts: ‘Now I desire to remind you, though you know all things once for all, that the Lord [some manuscripts read ‘Jesus’], after saving a people out of the land of Egypt, subsequently destroyed those who did not believe’ (Jude 1:5).

The early Christians also saw the Son’s role as creator and sustainer of all things, with and for the Father. Because the Son was how God spoke all things into being, the power of the Son upheld all things. Thus, ‘in him all things hold together’ (Col.1:17). Ingeniously, the author of the ‘Christ-hymn’ in Colossians 1:15 – 17 focuses upon the various meanings which can be gleaned from the first word of Genesis 1:1, ‘in the beginning of’ (beresith). Using three meanings of the Hebrew preposition be (‘in,’ ‘by,’ and ‘for’), ‘in the beginning of’ is amplified by the statement that all things were created ‘in’ Christ, ‘by’ Christ, and ‘for’ Christ. Furthermore, the Hebrew root resith has multiple meanings (‘beginning,’ ‘sum total,’ ‘head,’ and ‘first-fruits’). The author expounds upon these, saying that Christ ‘is before all things’ (beginning); ‘in him all things hold together’ (sum total); ‘he is the head of the body’ (head; source which supplies life); and he is ‘the firstborn from among the dead’ (first-fruits) (v.18). Jesus, therefore, fulfills every possible meaning of the very first word in the Bible.[40]

Thus, the early Christians in their entirety believed themselves to be preserving Jesus’ and the apostles’ true meaning when they said that Christ is the wisdom and power of God (1 Cor.1:24). It is exceedingly unlikely that Paul was the originator of this statement.

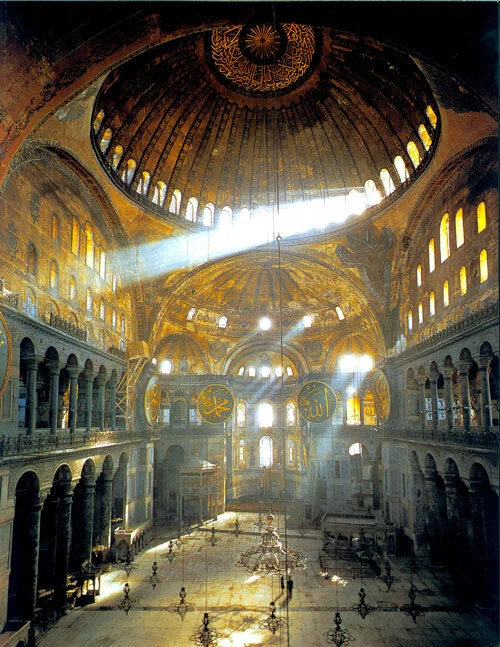

The impressive Hagia Sophia, considered the greatest cathedral of the Eastern Orthodox, is dedicated to Christ the Wisdom and Power of God. It still bears silent witness to that truth.

Therefore, theologically and exegetically, the term homoousion in the Nicene Creed of 325 AD, and the gradual convergence of Christian opinion around it, reaffirmed at Constantinople 381 AD, reflects the united Church resisting the Arian heresies, and insisting on a certain traditional understanding of the Father-Son relation which prevailed prior to Arius. That is, they were not simply saying that there is something akin to intangible ‘divine stuff’ that the Father has, which the Son has also. Rather, they were reasoning out the use of a difficult term with its own fascinating history – ousia – redeploying it for proper Christian use, as referring to unity of the divine essence/substance in the Father, Son, and Spirit. This reasoning was based, in part, on the conviction that the Son is the Father’s very Wisdom, and the Father’s own Power. In De Decretis, Athanasius gives the authoritative explanation for how the Nicene Council understood this term. And in Contra Arianos, he gives the explanation for how it is derived from Scripture.

The Nicene understanding of the Trinity, then, rules out any notion of separation between Father and Son at any time, including the cross. As I mentioned before, early church historian and theologian Lewis Ayres says the Nicene Christians would warn against making each Person of the Trinity out to have a separate mind. He correctly asserts that, for the early Christians, Father, Son, and Spirit know us and act towards the creation inseparably, in union with one another:

‘It is true that pro-Nicenes do intend to place restrictions on the way that we imagine the unity of God. Most clearly, if we were to imagine God as three potentially separable agents or three ‘centres of consciousness’ the contents of whose ‘minds’ were distinct, pro-Nicenes would see us as drawing inappropriate analogies between God and created realities and in serious heresy.’[41]

My study of early church teaching on the Son of God as the Wisdom of God and Power of God confirms Louis Ayres’ judgment. Ambrose of Milan (c.340 – 397 AD), a younger contemporary of Athanasius, says:

‘No separation, then, is to be made of the Word from God the Father, no separation in power, no separation in wisdom, by reason of the Unity of the Divine Substance. Again, God the Father is in the Son, as we oft-times find it written, yet [He dwells in the Son] not as sanctifying one who lacks sanctification, nor as filling a void, for the power of God knows no void. Nor, again, is the power of the one increased by the power of the other, for there are not two powers, but one Power; nor does Godhead entertain Godhead, for there are not two Godheads, but one Godhead. We, contrariwise, shall be One in Christ through Power received [from another] and dwelling in us.’[42]

Conclusion

So what will you do the next time you are asked to agree with the Nicene Creed?

[1] Thomas G. Weinandy and Daniel A. Keating, Athanasius and His Legacy: Trinitarian-Incarnational Soteriology and Its Reception (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2017), p.84

[2] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, book 2, chapter 16, paragraph 10

[3] Athanasius of Alexandria, De Incarnatione 7.4

[4] R.C. Sproul, Christ’s Descent into Hell, http://www.ligonier.org/learn/devotionals/christs-descent-into-hell/ last accessed December 10, 2013.

[5] Athanasius of Alexandria, De Incarnatione 6:7 – 10

[6] See Mako A. Nagasawa, Jesus’ Cry of Dereliction: Why the Father Did Not Turn Against or Away from the Son

[7] Athanasius of Alexandria, Contra Arianos 3.56

[8] Athanasius of Alexandria, De Decretis 20; cf.11, which says, ‘And on this account men in their time become fathers of many children; but God, being without parts, is Father of the Son without partition or passion; for there is neither effluence of the Immaterial, nor influx from without, as among men; and being uncompounded in nature, He is Father of One Only Son. This is why He is Only-begotten, and alone in the Father’s bosom, and alone is acknowledged by the Father to be from Him, saying, ‘This is My beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased [Matthew 3:17].’ And He too is the Father’s Word, from which may be understood the impassible and impartitive nature of the Father, in that not even a human word is begotten with passion or partition, much less the Word of God.’ This argument is seen in Christian arguments as early as Justin Martyr, Dialogue With Trypho 128, which dates to the early second century.

[9] Ibid 23

[10] Ibid 24

[11] Athanasius of Alexandria, Contra Arianos 1.11, 32; 2.37, 42, 62; 3.30, 48, 63 are explicit quotations. The implicit connections are far more numerous.

[12] Athanasius of Alexandria, Contra Arianos 1.19. This chapter has the densest use of the word ‘wisdom.’ Out of sixty eight total in Contra Arianos 1, Athanasius uses it a total of fourteen times in 1.19, whereas 1.5 (the next in density) has nine mentions, 1.28 has eight, 1.9 and 1.32 each have six, and the others have only two, one, or none at all.

[13] Athanasius of Alexandria, Contra Arianos 1.13, 14, 20, 22, 25, 27, 28, 46, 47, 49, 58, 60; 2.2, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 41, 42, 53 uses the sun and radiance image

[14] Athanasius of Alexandria, Contra Arianos 1.14, 19, 27; 2.2, 42, uses the fountain and stream image

[15] To see how Athanasius incorporates the Holy Spirit into this image, see Letters to Serapion on the Holy Spirit 1.19, ‘The Father is called fountain and light: ‘They have forsaken me,’ it says,’ the fountain of living water [Jeremiah 2:13]’… But the Son, in contrast with the fountain, is called river: ‘The river of God is full of water [Psalm 65:9]’… [And] we are said to drink of the Spirit. For it is written: ‘We are all made to drink of one Spirit [1 Corinthians 12:13]… Who can separate either the Son from the Father, or the Spirit from the Son or from the Father himself?’’

[16] Thomas Weinandy, Athanasius: A Theological Introduction (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2007), p.62 – 63 notes, ‘This appears to have been the common understanding prior to Nicea, in that Paul of Samosata earlier on, and now most recently Arius, claimed that such a view demanded change and division within the Godhead. Arius would, by this reading, be vindicated in that there would be no way that one could say that God is one and that the Son is God simultaneously.’

[17] Ibid, p.63 notes, ‘If one were an Origenist bishop or theologian, which many were, or an Arian sympathizer and so conceived, as was the tradition, the Father embodying or constituting the whole of the Godhead, and then were confronted with Nicea’s declaration that the Son is homoousios with the Father, it could very easily be alleged that what had been decreed was not simply that the Son is God as the Father is God, but that the Son is the Father since the Father alone defines and constitutes the one nature of God… [And thus] homoiousion was offered as a correction to Nicea so as to ensure the proper distinction between the Father and the Son.’

[18] Athanasius of Alexandria, Contra Arianos 1.19

[19] Athanasius of Alexandria, De Incarnatione 17.5 – 7

[20] Justin Martyr of Rome (c.100 – 165 AD), Dialogue with Trypho 61 writes, ‘I shall give you another testimony, my friends, from the Scriptures, that God begot before all creatures a Beginning, [who was] a certain rational power [proceeding] from Himself, who is called by the Holy Spirit, now the Glory of the Lord, now the Son, again Wisdom, again an Angel, then God, and then Lord and Logos… The Word of Wisdom, who is Himself this God begotten of the Father of all things, and Word, and Wisdom, and Power, and the Glory of the Begetter, will bear evidence to me…’ cf. 100, 126.

[21] Theophilus of Antioch (seventh bishop of Antioch, died 183 – 185 AD), Epistle to Autolycus 2.10, identifies ‘Wisdom’ with the Spirit and not the Son per se, although the point here is that (1) Theophilus still views Wisdom as a person of the Trinity, not as a quality spread out among the members of the Trinity, and (2) arguably he conceives of the Spirit as in the Son: ‘God, then, having His own Word internal within His own bowels, begot Him, emitting Him along with His own wisdom before all things. He had this Word as a helper in the things that were created by Him, and by Him He made all things. He is called governing principle [ἁρκή], because He rules, and is Lord of all things fashioned by Him. He, then, being Spirit of God, and governing principle, and wisdom, and power of the highest, came down upon the prophets, and through them spoke of the creation of the world and of all other things. For the prophets were not when the world came into existence, but the wisdom of God which was in Him, and His holy Word which was always present with Him.’ Cf.2.15 (‘In like manner also the three days which were before the luminaries, are types of the Trinity, of God, and His Word, and His wisdom’), 18 (‘But to no one else than to His own Word and wisdom did He say, Let Us make’), 22 (‘The God and Father, indeed, of all cannot be contained, and is not found in a place, for there is no place of His rest; but His Word, through whom He made all things, being His power and His wisdom…’)

[22] Irenaeus of Lyons (c.130 – 202 AD), Against Heresies, 4.7.4 follows Theophilus in identifying ‘wisdom’ with the Spirit: ‘For His offspring and His similitude do minister to Him in every respect; that is, the Son and the Holy Spirit, the Word and Wisdom…’; cf. 4.20.1 – 4.

[23] Tertullian of Carthage (c.155 – 240 AD), Adversus Praxean 4 writes, ‘I derive the Son from no other source than from the substance of the Father. I describe him as doing nothing without the Father’s will, as receiving all power from the Father. How then can I be abolishing from the faith that monarchy when I safeguard it in the Son, as handed down to the Son by the Father?’

[24] Clement of Alexandria (c.150 – c.215 AD), Paedagogus / The Instructor 1.2 writes, ‘But the good Instructor, the Wisdom, the Word of the Father, who made man, cares for the whole nature of His creature; the all-sufficient Physician of humanity, the Saviour, heals both body and soul.’ Cf. 3.12.

[25] Origen of Alexandria (c.184 – c.254 AD), De Principiis 1.1 writes, ‘in Your word and wisdom which is Your Son, in Himself we shall see You the Father’; in 2.1 writes, ‘The first-born, however, is not by nature a different person from the Wisdom, but one and the same. Finally, the Apostle Paul says that Christ (is) the power of God and the wisdom of God’; and in 2.2 writes, ‘it is once rightly understood that the only-begotten Son of God is His wisdom hypostatically existing.’

[26] Alexander of Alexandria (died 328 AD), Epistle to Alexander, Bishop of Constantinople, wrote, ‘They overthrow the testimony of the Divine Scriptures, which declare the immutability of the Word and the Divinity of the Wisdom of the Word, which Word and Wisdom is Christ.’ recorded by Theodoret of Cyrus, Ecclesiastical History 1.3.

[27] Methodius of Olympus (died 311 AD), From the Discourse on the Resurrection 1.15 writes, ‘The apostle certainly, after assigning the planting and watering to art and earth and water, conceded the growth to God alone, where he says, Neither is he that plants anything, neither he that waters; but God that gives the increase. [1 Corinthians 3:7] For he knew that Wisdom, the first-born of God, the parent and artificer of all things, brings forth everything into the world; whom the ancients called Nature and Providence, because she, with constant provision and care, gives to all things birth and growth. For, says the Wisdom of God, my Father works hitherto, and I work. [John 5:17] Now it is on this account that Solomon called Wisdom the artificer of all things, since God is in no respect poor, but able richly to create, and make, and vary, and increase all things.’

[28] Council of Sardica of 343 AD, attended by between 170 and 250 bishops, confessed, ‘We confess that the Word is Word of God the Father, and that beside Him there is no other. We believe the Word to be the true God, and Wisdom and Power. We affirm that He is truly the Son, yet not in the way in which others are said to be sons…’ recorded by Theodoret of Cyrus, Ecclesiastical History 2.6

[29] Cyril of Jerusalem (c.313 – 386 AD), Catechetical Lectures, Lecture 4.7, writes, ‘Believe also in the Son of God, One and Only, our Lord Jesus Christ, Who was begotten God of God, begotten Life of Life, begotten Light of Light , Who is in all things like to Him that begot, Who received not His being in time, but was before all ages eternally and incomprehensibly begotten of the Father: The Wisdom and the Power of God, and His Righteousness personally subsisting : Who sits on the right hand of the Father before all ages.’ Lecture 6.18, ‘For the Wisdom of God is Christ His Only-begotten Son…’

[30] Hilary of Poitiers (c.310 – c.367 AD), On the Trinity 2.10, writes, ‘Listen then to the Unbegotten Father, listen to the Only-begotten Son. Hear His words, The Father is greater than I [John 14:28], and I and the Father are One [John 10:30], and He that has seen Me has seen the Father also [John 14:9], and The Father is in Me and I in the Father [John 14:10], and I went out from the Father [John 16:28], and Who is in the bosom of the Father [John 1:18], and Whatsoever the Father has He has delivered to the Son [John 5:20 – 29], and The Son has life in Himself, even as the Father has in Himself [John 5:26]. Hear in these words the Son, the Image, the Wisdom, the Power, the Glory of God.’

[31] Ambrose of Milan (c.340 – 397 AD), Exposition of the Christian Faith 1.16, writes, ‘Further, that none may fall into error, let a man attend to those signs vouchsafed us by holy Scripture, whereby we may know the Son. He is called the Word, the Son, the Power of God, the Wisdom of God. The Word, because He is without blemish; the Power, because He is perfect; the Son, because He is begotten of the Father; the Wisdom, because He is one with the Father, one in eternity, one in Divinity.’ Cf. 1.62; 2.143; 5.194 – 196; 4.43, writes, ‘Now is there anything impossible to God’s Power and Wisdom? These, observe, are names of the Son of God’

[32] Basil of Caesarea (c.329 – 379 AD), On the Holy Spirit 1.19 writes, ‘For the Father is not regarded from the difference of the operations, by the exhibition of a separate and peculiar energy…’; 1.20, ‘all things that the Father has belong to the Son, not gradually accruing to Him little by little, but with Him all together and at once’; cf. 1.15.

[33] Gregory of Nyssa (c.335 – 395 AD), Against Eunomius 1.24, writes, ‘But in the case of the divine nature, because every perfection in the way of goodness is connoted with the very name of God, we cannot discover, at all events as we look at it, any ground for degrees of honour. Where there is no greater and smaller in power, or glory, or wisdom, or love, or of any other imaginable good whatever, but the good which the Son has is the Father’s also, and all that is the Father’s is seen in the Son, what possible state of mind can induce us to show the more reverence in the case of the Father? If we think of royal power and worth the Son is King: if of a judge, ‘all judgment is committed to the Son :’ if of the magnificent office of Creation, ‘all things were made by Him :’ if of the Author of our life, we know the True Life came down as far as our nature: if of our being taken out of darkness, we know He is the True Light, who weans us from darkness: if wisdom is precious to any, Christ is God’s power and Wisdom.’ Cf. 2.1, 4, 12; 3.2. On the Holy Spirit: ‘the fountain of power is the Father, and the power of the Father is the Son…’

[34] Gregory of Nazianzus (c.340 – 397 AD), Fourth Theological Oration 20, writes, ‘In my opinion He is called Son because He is identical with the Father in Essence; and not only for this reason, but also because He is Of Him… And He is called the Word, because He is related to the Father as Word to Mind; not only on account of His passionless Generation, but also because of the Union, and of His declaratory function. Perhaps too this relation might be compared to that between the Definition and the Thing defined… For, it says, he that has mental perception of the Son (for this is the meaning of Hath Seen) has also perceived the Father; and the Son is a concise demonstration and easy setting forth of the Father’s Nature… He is also called Wisdom, as the Knowledge of things divine and human. For how is it possible that He Who made all things should be ignorant of the reasons of what He has made? And Power, as the Sustainer of all created things, and the Furnisher to them of power to keep themselves together. And Truth, as being in nature One and not many (for truth is one and falsehood is manifold), and as the pure Seal of the Father and His most unerring Impress. And the Image as of one substance with Him, and because He is of the Father, and not the Father of Him. For this is of the Nature of an Image, to be the reproduction of its Archetype, and of that whose name it bears; only that there is more here. For in ordinary language an image is a motionless representation of that which has motion; but in this case it is the living reproduction of the Living One, and is more exactly like than was Seth to Adam, or any son to his father.’

[35] John Chrysostom of Constantinople (349 – 407 AD), Homilies on 1 Corinthians, Homily 7:1, writes, ‘Since therefore he had affirmed His power to be so great, and had referred the whole unto the Son, saying that He had become wisdom unto us… [And] As if he had said, He gave unto us Himself.’ (emphasis mine); and in 7:5, ‘By the name of wisdom, he calls both Christ, and the Cross and the Gospel.’

[36] Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430 AD), On the Trinity 1.10, writes, ‘For neither has the Son separated the Father from Himself, because He Himself, speaking elsewhere with the voice of wisdom (for He Himself is the Wisdom of God) says…’

[37] Ben Witherington III, Matthew: Smyth & Helwy’s Bible Commentary (Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwy’s Publishing, Inc., 2006), p.238.

[38] Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 113

[39] Justin Martyr, First Apology 62

[40] See F. F. Bruce, The Epistles to the Colossians, to Philemon, and to the Ephesians, NICNT (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1984), p.68; C. J. H. Wright, ‘Family,’ Anchor Bible Dictionary 2:765–9, 765 for ‘and he is ‘the firstborn from among the dead’ (first-fruits) (v. 18). ‘As the one part representing the whole of God’s people he ensures our resurrection (1 Cor 15:23)’ from David E. Garland, Colossians and Philemon, NIVAC (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1998), 85.

[41] Lewis Ayres, Nicaea and its Legacy: An Approach to Fourth-Century Trinitarian Theology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), p.296

[42] Ambrose of Milan, Exposition of the Christian Faith 2.36